Who was Wassily Kandinsky?

Wassily Kandinsky, a Russian painter and art theorist, is recognized as a pioneering figure in avant-garde art and one of the creators of pure abstraction in painting during the early 20th century. Kandinsky utilized the expressive connection between color and shape to generate an aesthetic encounter that captivated the audience’s visual perception, auditory senses, and emotional responses. He believed that complete abstraction provided the potential for deep, transcendent expression and that replicating from nature hindered this process. Driven by a strong desire to convey a universal feeling of spirituality through his art, he developed a unique visual language loosely connected to the external world. Still, he effectively conveyed the artist’s profound inner experience. His visual lexicon evolved through three stages, transitioning from his initial figurative paintings and their celestial symbolism to his ecstatic and dramatic compositions and finally to his later geometric and organic two-dimensional color fields.

Kandinsky’s ideas and techniques have substantially influenced subsequent generations of artists. His use of color and structure to convey spiritual and emotional concepts profoundly impacted the artistic endeavors of figures like Mark Rothko and Jackson Pollock. His focus on abstraction and the utilization of color as a means of conveying emotions have inspired other painters to explore non-representational art styles. The works of abstract expressionists such as Willem de Kooning and Joan Mitchell reflect his influence.

Early Life and Inspirations

Wassily Kandinsky was born in Moscow to Lidia Ticheeva and Vasily Silvestrovich Kandinsky, who worked as a tea merchant. One of his great-grandmothers was Princess Gantimurova. Kandinsky acquired knowledge from diverse sources during his time in Moscow. In Odessa, where his parents established residence in 1871, he finished his secondary education and pursued his interest in music by becoming a self-taught pianist and cellist. In addition, he pursued painting as a hobby and later reminisced about an early inclination towards abstraction, stemming from his belief during adolescence that each color had an enigmatic vitality.

Kandinsky enrolled in the University of Moscow in 1886 to study law and economics. Still, he never stopped feeling strangely drawn to color while admiring the city’s vibrant architecture and icon collections, which he once said contained the inspiration for his work. In 1889, the university assigned him on an anthropological expedition to the province of Vologda, located in the densely wooded northern region. As a result, he developed a long-lasting fascination with the non-realistic artistic techniques employed in Russian folk painting. As a child, he remembers being captivated and invigorated by color. His enduring interest in the symbolism and psychology of color persisted as he matured.

The Path to Abstraction

Kandinsky’s artistic perspective was profoundly shaped by his spiritual and mystical ideas. His fascination with spirituality originated during his early years when he was exposed to theosophy, a religious movement that aimed to reconcile science and religion. Subsequently, he developed a keen interest in the writings of the Russian mystic Madame Blavatsky, whose concepts of spiritual progression and the interconnectedness of all faiths profoundly impacted him.

Spiritual and Philosophical Underpinnings

The exhibition “Kandinsky: Path to Abstraction” was hailed as the inaugural showcase in Britain dedicated to the paintings of Wassily Kandinsky. The exhibition commences by highlighting the initial phase of his work, with a collection of early landscapes influenced by the captivating scenery of Bavaria and the folk motifs found in Russian fairy tales and legends. Subsequently, the text delves into the progression of Kandinsky’s artistic style following his relocation to Germany and his pivotal role in co-founding the revolutionary artistic collective known as Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) group. This phase significantly impacted his creative output, and during this period, Kandinsky started to envision painting as an alternate means to access spiritual truth. Gradually, he eliminated descriptive details by simplifying recognizable motifs, such as hilltop castles and riders on horseback, into calligraphic lines. Simultaneously, he started incorporating expansive swaths of vivid hues to evoke emotions linked to classical music and elicit responses that the deliberate selection of particular colors might influence.

The exhibition also delves into the artistic transformations when Kandinsky relocated to Russia and later returned to Germany, where he joined the Bauhaus movement. Kandinsky’s latter works were significantly influenced by contemporary developments in Russian avant-garde art and Bauhaus design, further shaping his abstract language.

Pioneering Works in Abstraction

The pioneering works in abstraction include: Composition VII, On White II, and Composition X.

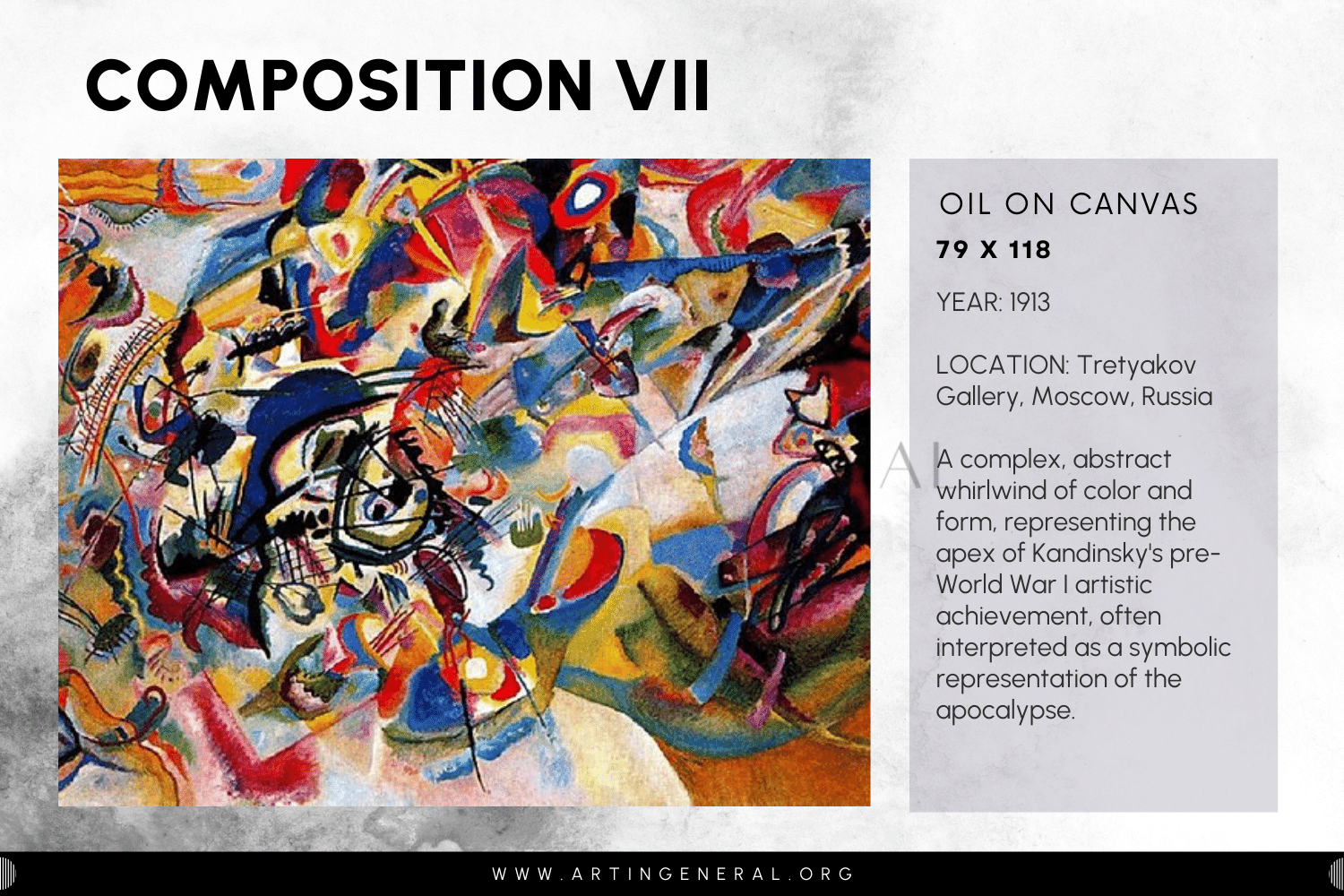

Composition VII demonstrates the artist’s refusal to depict things realistically using a dynamic combination of vibrant colors and abstract shapes. Kandinsky removed conventional depictions of depth and exposed the abstracted symbols, intertwining various hues and shapes to convey universal themes and feelings shared by all nations and observers.

Composition VII

On White II

On White, II depicts Wassily Kandinsky’s vibrant and dynamic eruption of color and form emanating from the heart of a blank white canvas. The composition is visually appealing, with a lively burst of angular lines, colors, and patterns. Although there are no explicit items depicted, it is evident that there is an underlying activity taking place.

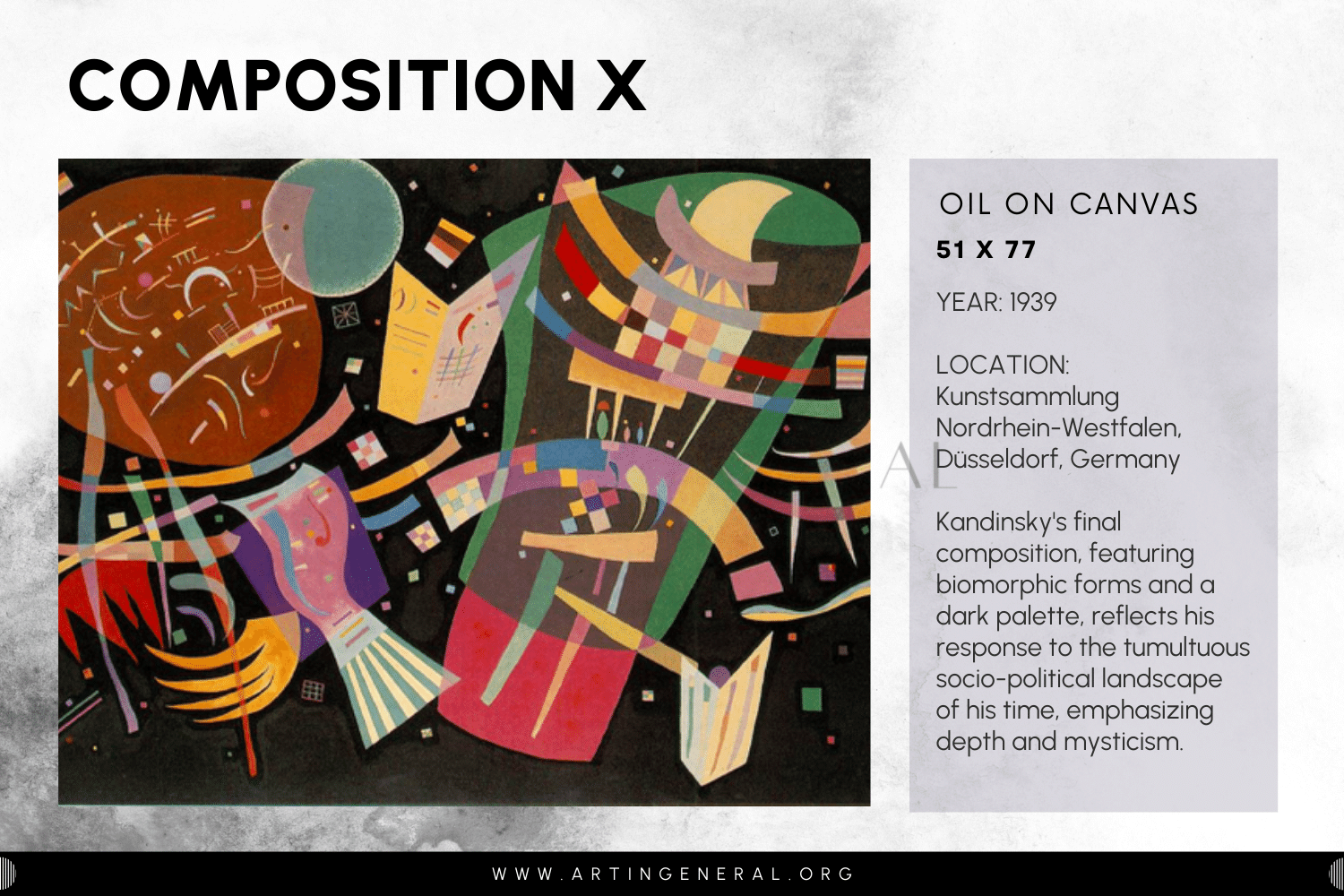

Composition X

Composition X uses a black background to enhance the visual intensity of the vividly colored undulating shapes in the foreground. The black expanse holds great significance, as Kandinsky seldom employed this color. It evokes both the vastness of the cosmos and the somberness associated with the end of life. The fluctuating surfaces of hue evoke microscopic organisms and convey the profound emotional and spiritual sensations that Kandinsky encountered towards the conclusion of his life.

Technique and Style

Wassily Kandinsky’s artworks often showcase vibrant colors, dynamic lines, and geometric shapes. He employed these elements to generate visual harmonies and rhythms that reflected the structure and cadence inherent in music. Kandinsky regarded painting as a transcendent expedition, aiming to communicate timeless verities and access the profound realms of human awareness. He believed colors were symbolic and could elicit distinct spiritual and emotional states. Kandinsky’s abstract compositions aimed to evoke thought, reflection, and transcending the physical realm.

Influence of the Blue Rider Group

The Blue Rider was a collective of artists Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc that was formed to organize exhibitions and publish their works. The name “Der Blaue Reiter” was chosen by the artists based on Marc’s affinity for horses, Kandinsky’s fascination with the symbolism of the rider, and their shared preference for the color blue. The group advocated for advancing contemporary art and the potential for spiritual enlightenment through the symbolic connections of music and color – two topics that deeply resonated with Kandinsky.

Challenges and Controversies

The start of World War I in 1914 resulted in the disbandment of Der Blaue Reiter. However, despite their brief existence, the ensemble played a pivotal role in creating and profoundly influencing the renowned German Expressionist style. Following Germany’s declaration of war on Russia, Kandinsky was compelled to depart from the nation. He embarked on a journey to Switzerland and Sweden alongside Munter, which lasted for nearly two years. However, he ultimately made his way back to Moscow in early 1916.

Following the October Revolution in 1917, Kandinsky’s intentions to establish a personal, educational institution and creative space were disrupted by the Communist redistribution of private assets. Consequently, he collaborated with the new government to develop arts institutions and educational facilities. Architect Walter Gropius invited Kandinsky in 1921, urging him to come to Germany and teach at the Weimar Bauhaus. The prominent use of geometric shapes characterized Kandinsky’s artistic vocabulary at the Bauhaus. As an artist seeking to discover a universal aesthetic language, he intensified his utilization of overlapping, two-dimensional surfaces and well-defined forms.

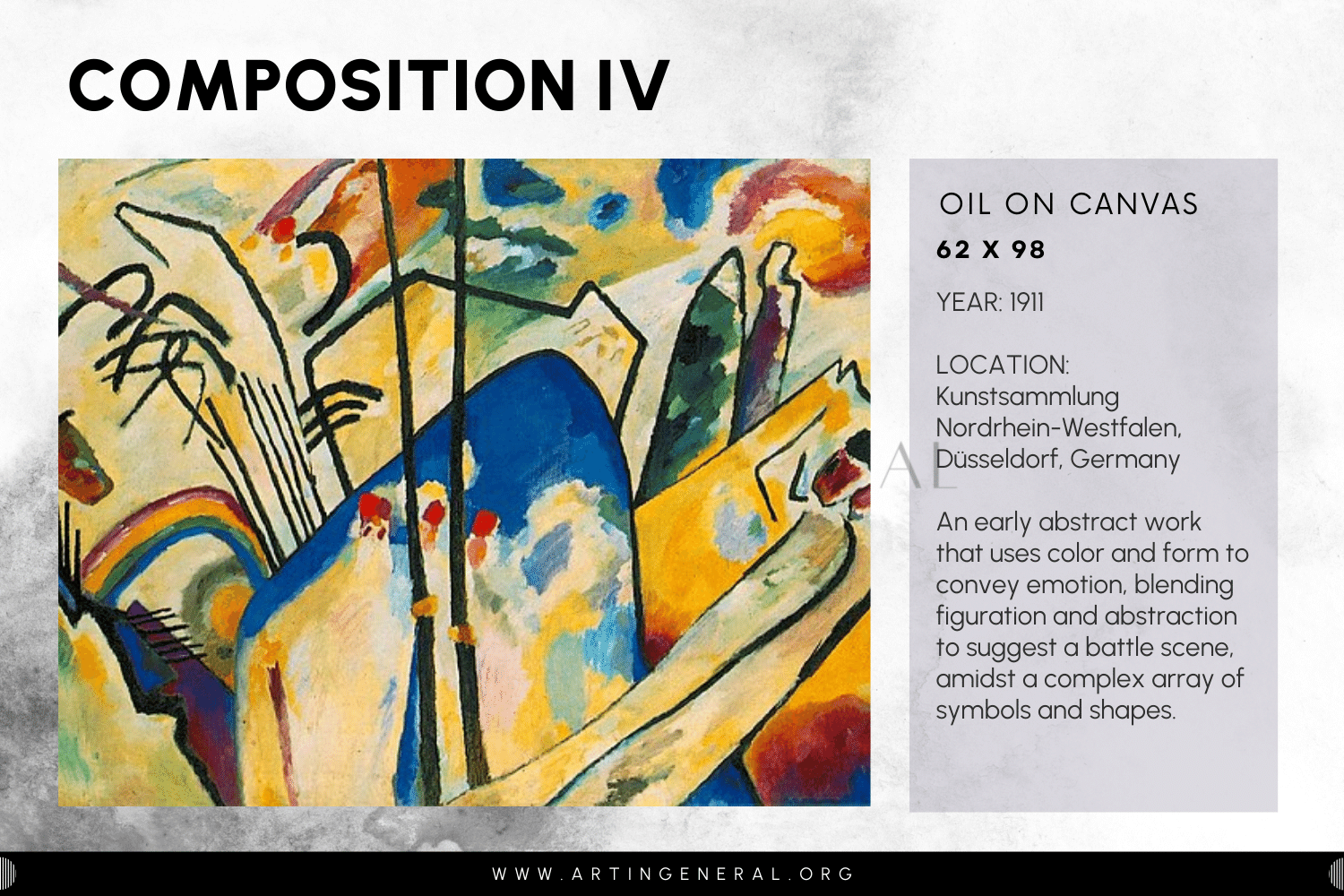

Composition IV

Year: 1911

Medium: Oil on canvas

In Composition IV, Kandinsky depicted elements such as Cossacks with lances, boats, reclining individuals, and a fortress on a hilltop amidst the vibrant colors and distinct black lines. Like other artworks from this era, he depicted the cataclysmic conflict that would result in everlasting tranquility. The presence of the Cossacks depicts the concept of conflict, while the serenity of the graceful shapes and reclining humans on the right suggests the forthcoming tranquility and salvation.

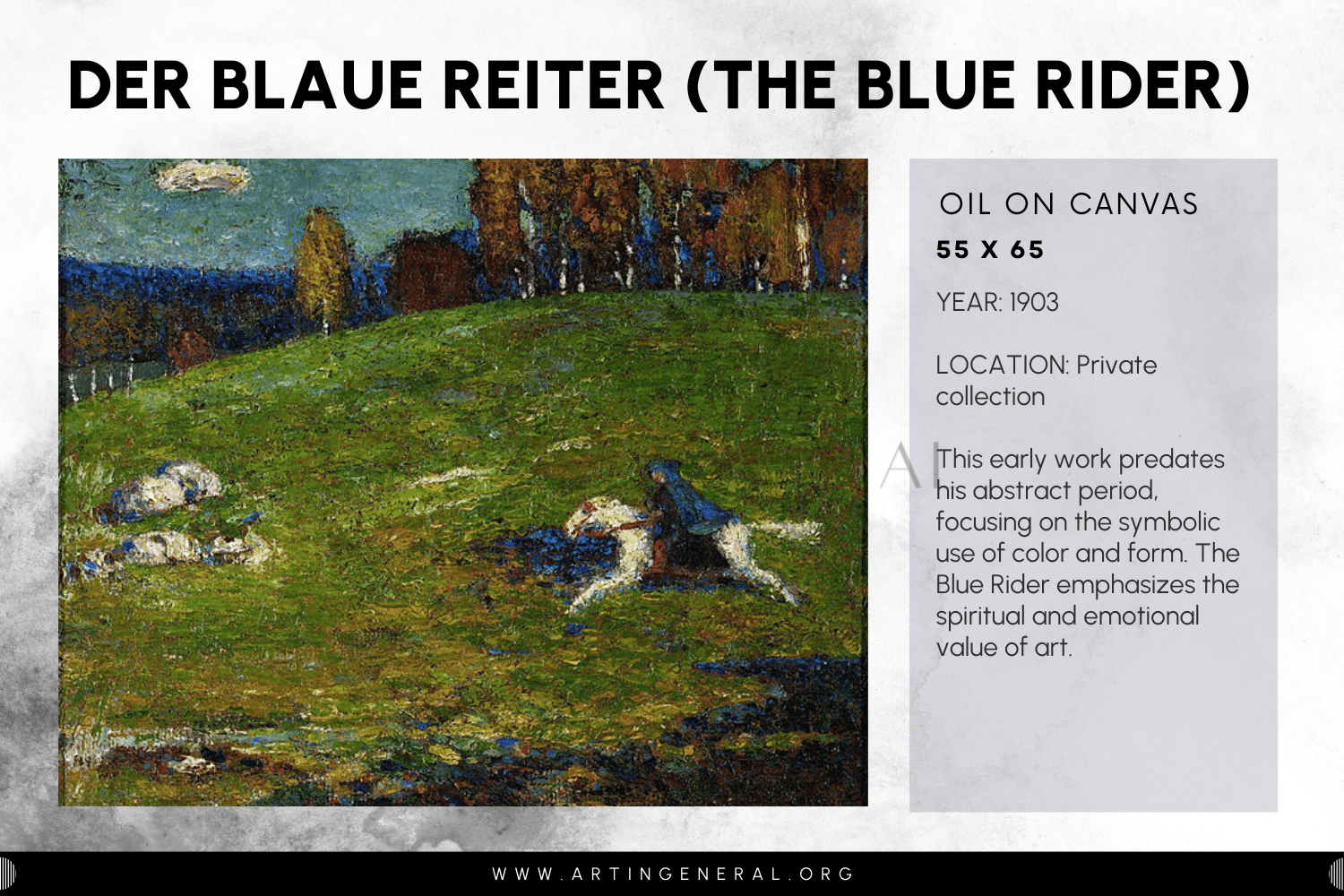

Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider)

Year: 1903

Medium: Oil on canvas

Der Blaue Berg is an uncomplicated depiction – a solitary rider dashing across a scenery – yet symbolizes a crucial juncture in Kandinsky’s evolving artistic approach. In this artwork, he showcased a distinct stylistic connection to the Impressionists, such as Claude Monet. This is especially apparent in the juxtaposition of light and shadow on the hillside illuminated by the sun. The indeterminacy of the form of the equestrian figure depicted in many colors that nearly integrate anticipates his inclination towards abstraction.

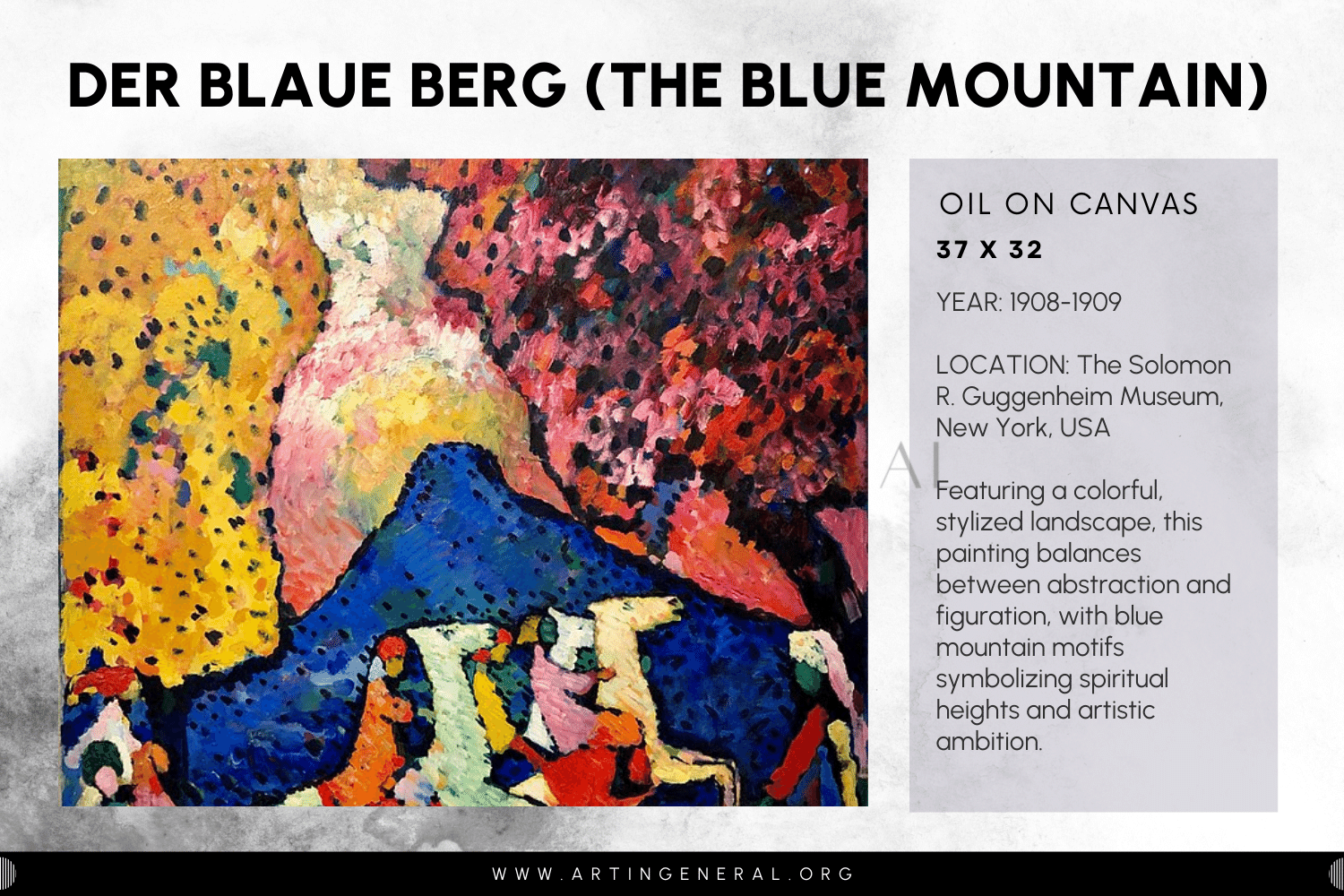

Der Blaue Berg (The Blue Mountain)

Year: 1908-09

Medium: Oil on canvas

In Der Blaue Berg, Fauves influenced Kandinsky’s color palette, as evidenced by his distortion of color and departure from nature. He displayed a vivid blue mountain with red and yellow trees framing it on both sides. Horseback horse riders gallop across the area in the foreground. The horse riders signify the possibility of salvation after the world’s end, even as they also portend the widespread devastation of the end times.

Rather than inspiring a sense of hopelessness, Kandinsky’s vivid color and expressive brushwork inspire hope in the viewer. In addition, the dazzling colors and deep contours evoke his passion for Russian folk art. Kandinsky advanced toward pure abstraction due to this highly symbolic and figurative composition.

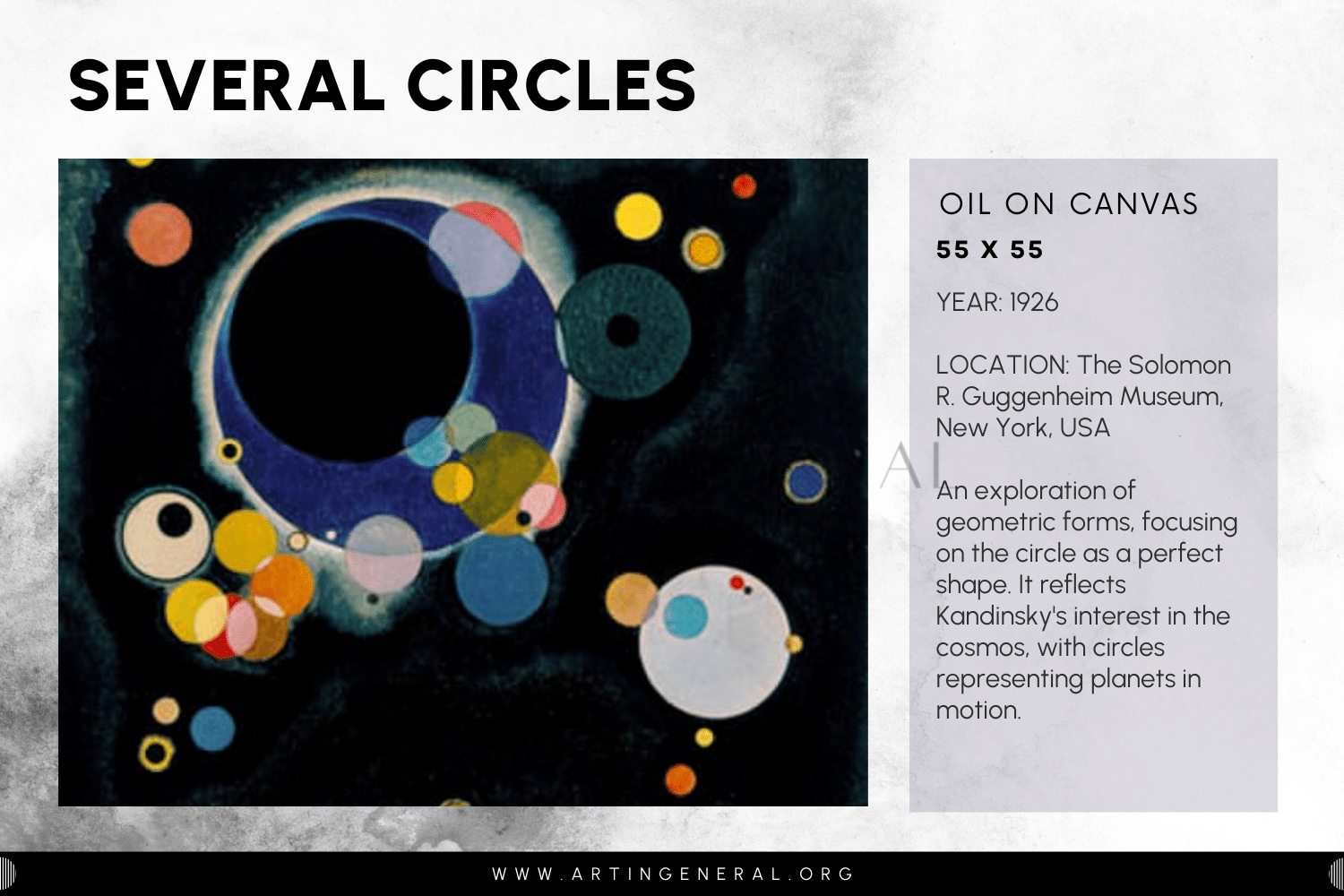

Several Circles

Year: 1926

Medium: Oil on canvas

Several Circles was created due to the artist’s exploration of a linear painting approach, demonstrating his fascination with the circular form. In this work, he utilized the diverse potential interpretations of the circle to establish a feeling of spiritual and emotional unity. Kandinsky skillfully balances each circle’s various dimensions and vibrant colors, allowing them to emerge from the canvas through meticulous juxtapositions of proportion and color. The round shapes’ dynamic movement recalls their global nature, ranging from celestial stars to tiny dew droplets. The circle, an essential shape, is deeply intertwined with life.

Kandinsky’s Legacy and Influence

Kandinsky’s creative and theoretical contributions significantly influenced the philosophical basis of subsequent modern movements, notably Abstract Expressionism and its variations, such as Color Field Painting. The late biomorphic artwork of the artist had a significant impact on the artistic growth of Arshile Gorky, leading to the development of a non-objective style that played a role in shaping the aesthetic of the New York School. Jackson Pollock was intrigued by Kandinsky’s latter artworks and captivated by his beliefs on the expressive potential of art, particularly his focus on spontaneous activity and the subconscious mind. Kandinsky’s examination of the sensory characteristics of color had a profound impact on Color Field artists, such as Mark Rothko, who focused on the connections between different shades to evoke emotions. Artists of the Neo-Expressionist movement in the 1980s, such as Julian Schnabel and Philip Guston, incorporated his concepts of the artist’s inward expression on the canvas into their postmodern artwork.

The Bauhaus Period

At the Bauhaus Art School, Kandinsky taught students in foundational classes focused on abstract form elements and analytical drawing. While at Bauhaus, he deliberately investigated the spiritual attributes of color and shape. With his experience, students delved into the basics of design and explored his innovative color theory, which was rooted in the principles of form psychology. Geometric shapes became prominent in his artistic style, as shown in Composition viii, which he painted at Bauhaus.

Preserving Kandinsky’s Heritage

Kandinsky’s artworks are featured in museum collections worldwide, particularly at prestigious institutions such as the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and the Centre Pompidou in Paris.

Kandinsky in Modern Culture

Wassily Kandinsky’s artistic contributions played a crucial role in legitimizing abstraction as a valid mode of creative communication, hence opening up opportunities for subsequent generations of artists to experiment with novel forms and approaches. He ushered in a new era of artistic exploration by challenging conventional ideas of representation through his use of color and shape. Kandinsky’s paintings are replete with references to music. He thought that hues affected the spirit and resonated with one another to create visual “chords.”

Leave a Reply