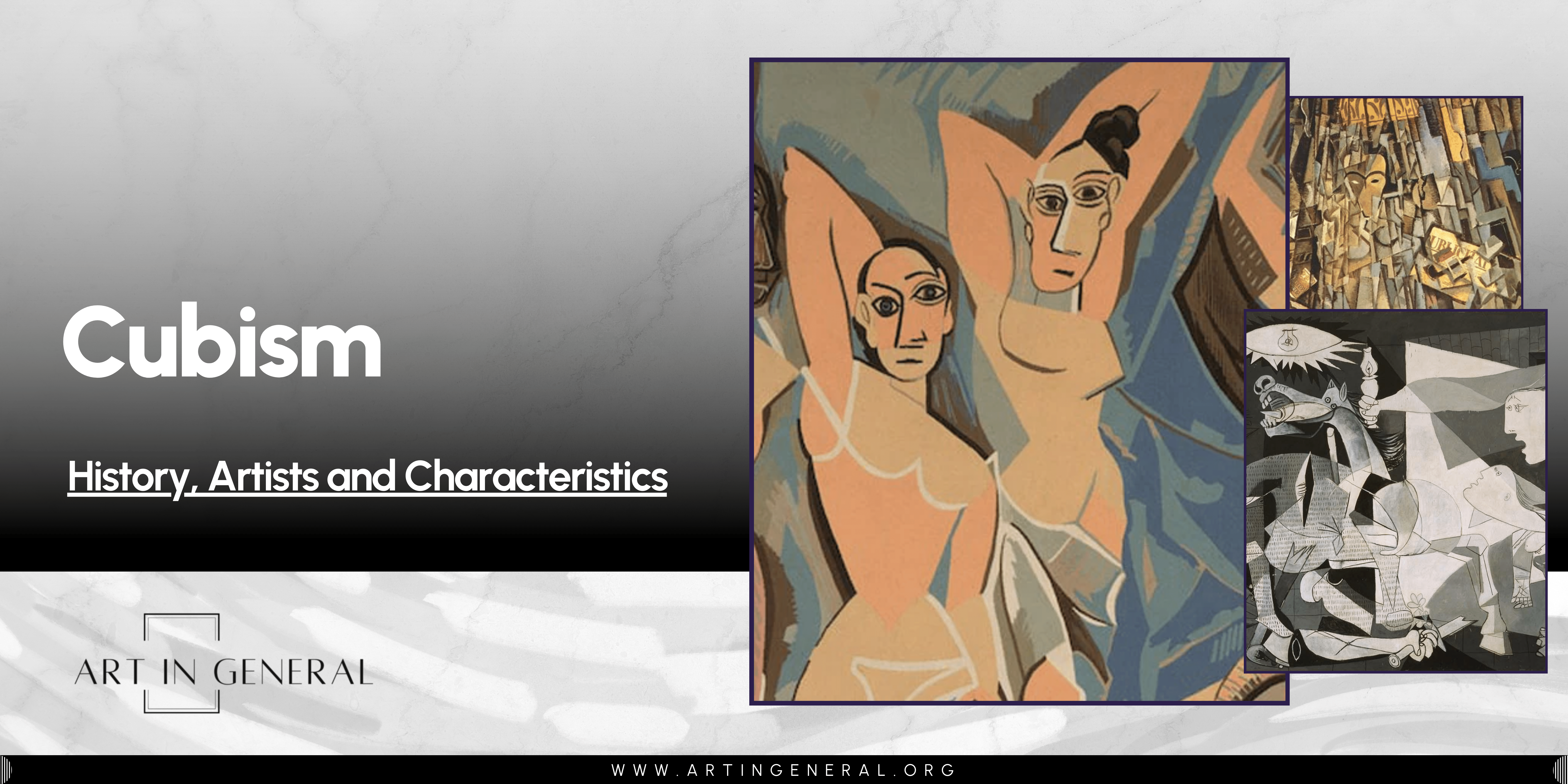

Cubism is an art movement that began at the beginning of the 20th century in Paris. It involves fragmenting forms into geometrical shapes so that abstraction and representation are counterbalanced. A single piece often brought about an unsettling effect by establishing several points of view. Initially, this was limited to a two-dimensional flat surface, but it eventually expanded to three dimensions.

Cubism began in Paris at the beginning of the 20th century, in the studios of Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. Between 1905 and the start of the First World War was when the movement took place. Paul Cézanne’s later paintings, in which he appears to be painting subjects from slightly varied perspectives, impacted cubism. Pablo Picasso also drew inspiration from African tribal masks, which portray a vivid human image despite being highly stylized or non-naturalistic.

Among the notable painters associated with the Cubist movement are its forefathers, Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, as well as Juan Gris, Jacques Lipchitz, Robert Delaunay, Albert Gleizes, Fernand Leger, and Jean Metzinger.

Major Cubist paintings include Les Desmoiselles d’Avignon (1907), Violin and Palette (1909), Guernica (1927), Three Women (1921), The Weeping Woman (1937), Cubist Self-Portrait (1923) and Electric Prisms (1914).

The Birth of Cubism: Historical Context

Beginnings of the Cubism art movement (1904-1907)

Cubism was started in 1907 by artists Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. French poet Apollinaire introduced the two in 1907, and they began collaborating nearly every day. They were also influenced by African art, Iberian sculpture, and Paul Cézanne’s Post-Impressionist paintings. The pre-Cubist era is referred to as Cézanian Cubism or Proto-Cubism.

The goal of merging several perspectives into a single image rather than adhering to conventional notions of perspective was one of cubism’s central tenets. This was accomplished by breaking an item into planes so the various viewpoints would convey the sense of three dimensions without illustrating any depth on the canvas. Emphasizing the canvas’s two-dimensionality was another aspect of the cubist style.

Development of the Cubism movement (1907-1914)

In the 1910s, Cubism rapidly expanded throughout Europe, partly thanks to its systematic approach to creating images and its flexibility in presenting items in novel ways. The two primary phases of Cubism, Analytic Cubism and Synthetic Cubism, were founded by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, and they peaked between 1907 and 1912 and 1912 and 1914, respectively.

Analytic Cubism was characterized by the breaking up of the things portrayed or the disintegration of the image space. In this approach, the viewer was provided with a three-dimensional view, or views on the two-dimensional surface, by breaking down or “analyzing” the objects and the pictorial space.

The incorporation of collage and papier collé elements characterized Synthetic Cubism. This phase connected high and low art worlds, the ostensibly worthless leftovers from daily existence.

There was considerable dissent among critics regarding whether the primary objective of Cubists was to expose the essence of imagery through more objective representation or whether distortion and abstraction were their primary concerns. Because of its unusual concept and style, Cubism was rejected by many art academies, galleries, and established artists.

End/legacy of the movement (1920s)

The end of Cubism was in the early 1920s. With the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, the initial Cubist movement began to transform. Cubists started to adopt a more abstract approach, which ultimately resulted in the creation of sub-genres within the movement, including Transparent Cubism and Abstract Cubism. Cubism’s influence persisted in art movements such as Abstract Expressionism, Constructivism, Futurism, and Surrealism.

How did the socio-political climate of 19th-century France give rise to Cubism?

The socio-political climate of France in the early 20th century significantly influenced the development of Cubism. Significant occasions and occurrences predominantly laid the basis for this revolutionary artistic movement. An essential element was France’s swiftly evolving metropolitan landscape, especially in Paris. Rapid renovation was taking place in the city, and the 1889 completion of the Eiffel Tower is a vivid reminder of this change.

What technological advancements influenced Cubism techniques?

In the late 1800s, technology advanced rapidly as discoveries such as telephones, cars, planes, and cameras reinforced the effects of the Industrial Revolution in Europe. As new art forms were embraced, some artists found it more difficult to reconcile their feelings and anxieties about industrialization and uncertain times through representational art.

Characteristics of Cubism

Characteristics of Cubism include: the broken picture plane, multiple perspectives, three-dimensional rendering, and simultaneity.

The Broken Picture Plane

The fragmented picture plane of cubism eschewed the academic art of the 19th century’s sheer surface and highly polished finish. The Cubist shapes appear to protrude and recede from the viewer’s reality. There isn’t a uniform texture throughout; instead, the forms are broken apart and relate syntactically to the omissions and gaps in the space.

Multiple Perspectives

The various viewpoints popular in Cubism challenged the traditional one-point view that had been the norm in art since the Renaissance. Although Paul Cézanne and Édouard Manet had already rejected linear perspective, the Cubists did it in their unique way by analyzing space and objects in a way that allowed for several views of the object simultaneously, within each angle and plane that made it up.

Three Dimensions

Cubism’s use of various viewpoints is tied to its three-dimensional depiction. The figure or item is painted with such detail that the painting appears to have a physical substance to it for all the

Simultaneity

The simultaneity of cubism is contingent upon time. A viewer’s request to complete the work’s holistic vision in his own time and location is conveyed through fragmentary items, traces of hands, and examined heads. These pieces demonstrate the convergence of many angles, forms, and textures, but they also signify the convergence of time by uniting their different “moving parts.”

How did Cubism artists revolutionize the use of light and color?

Cubism offered an alternative to conventional color schemes. During the synthetic phase of the movement, Cubism artists adopted a lively and varied color scheme, whereas its early phase emphasized subdued and monochrome hues. Artists like Juan Gris broke out from the constraints of naturalistic color representation by incorporating vibrant colors into their works.

The juxtaposition of clashing hues within a single composition was another technique used by cubist painters to create visual tension and encourage viewers to study objects and subjects from several angles simultaneously.

Pioneers and Icons of Cubism

Some of the major Cubist painters and makers include: Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, and Juan Gris.

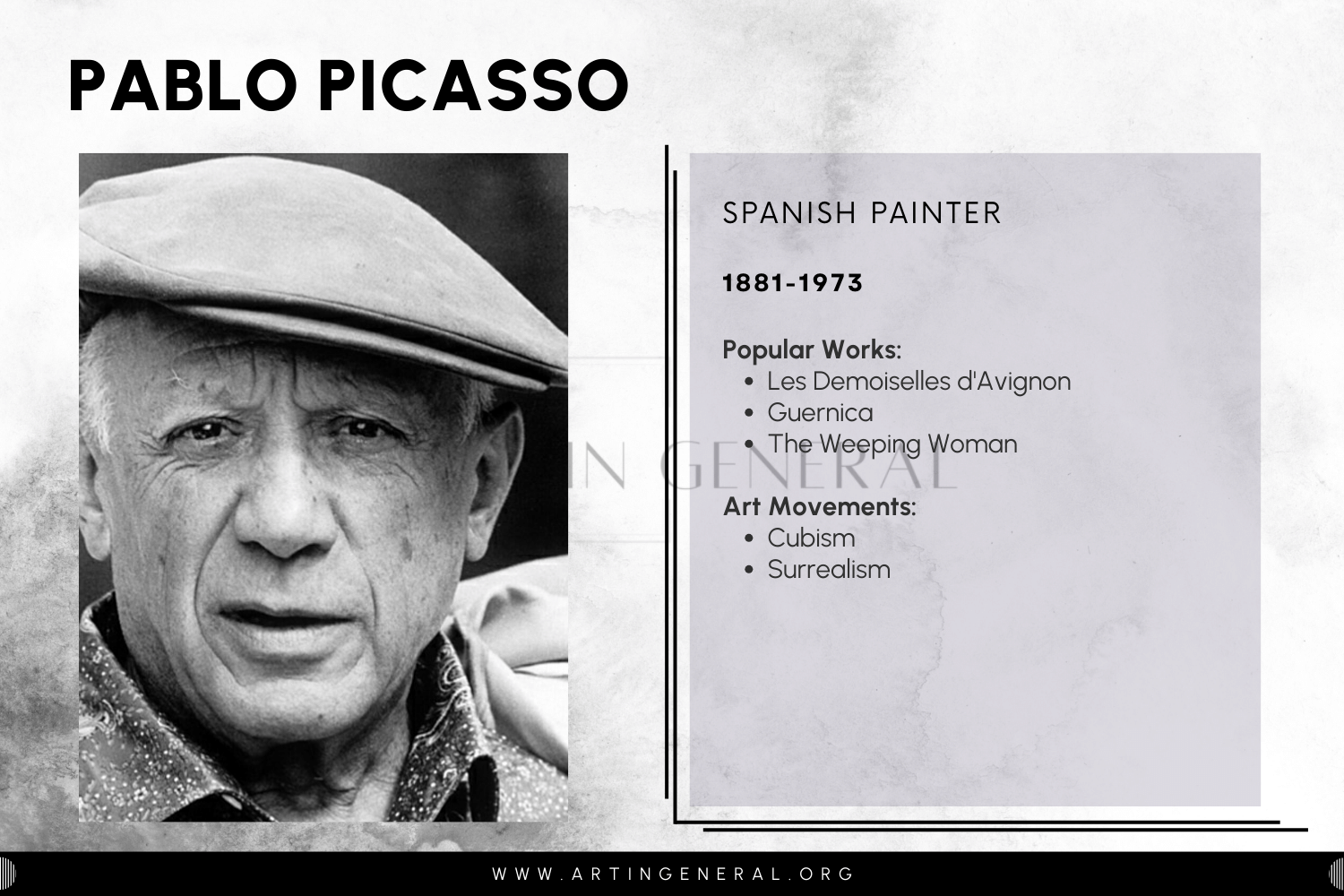

Pablo Picasso (1881-1973)

Pablo Picasso was born in Spain, although he lived and worked in Paris for the better part of his career. Picasso was greatly influenced by Paul Cézanne, African art, and Iberian sculpture. He and Georges Braque created Cubism in the middle of the first decade of the 1900s.

Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque collaborated so closely that it is nearly impossible to discern between their analytic phase of Cubism. They created serene paintings of three-dimensional forms that have been disassembled and reconstructed in shallow space, using subdued hues. However, there is a discernible distinction in the modeling between the two. Picasso’s analytical shapes are generally more sculptural and substantial, whereas Braque’s are more lighthearted and ethereal.

Over time, Pablo Picasso’s Cubism changed, moving from the early analytic Cubism to the synthetic period and ultimately combining Cubism with irrational surrealist aspects. Picasso’s major pieces are Weeping Woman (1937), The Aficionado (1912), and Girl with a Mandolin (Fanny Tellier) (1910).

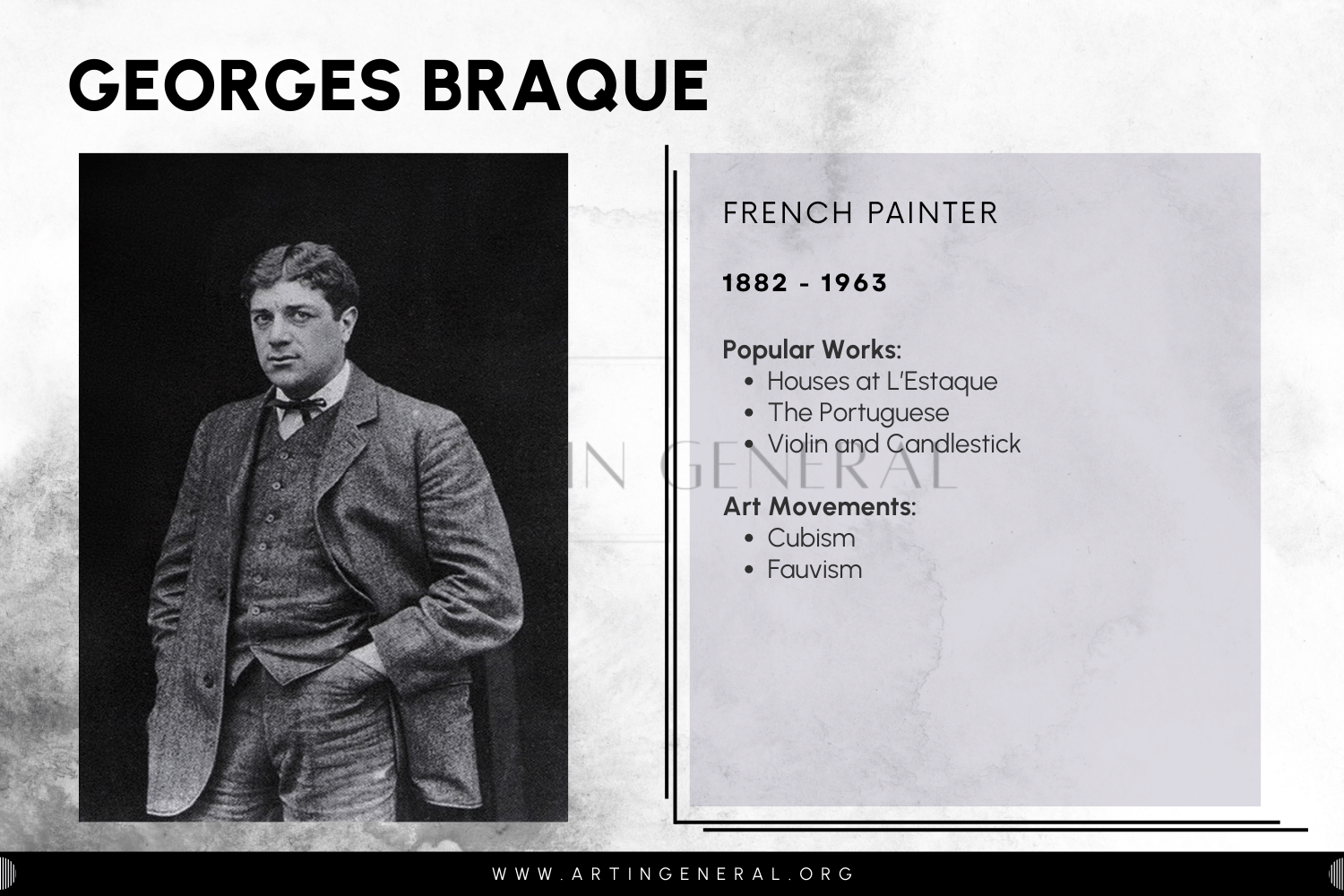

Georges Braque (1882-1963)

Georges Braque was a French artist who worked in Paris for the majority of his career. Braque was instrumental in laying the groundwork for the emerging Cubist movement alongside Pablo Picasso in the first decade of the 1900s.

Georges Braque was greatly influenced by the aesthetic legacy of Cézanne’s diverse viewpoints. Compared to Picasso, Braque’s Cubism is more serene and contemplative. Despite this, it is challenging to distinguish between many of their images, especially during the analytical cubism phase, which was marked by a very close mutual influence. But until much later in his career, Georges Braque was more contemptuous of color than Pablo Picasso.

Georges Braque’s apolitical Cubism, which focused on still lifes with drinking containers and musical instruments, was another distinction. Picasso, on the other hand, made many social and political allusions. His notable works include Violin and Candlestick (1910), Pitcher and Violin (1909–10), and Fruit Dish (1908–9).

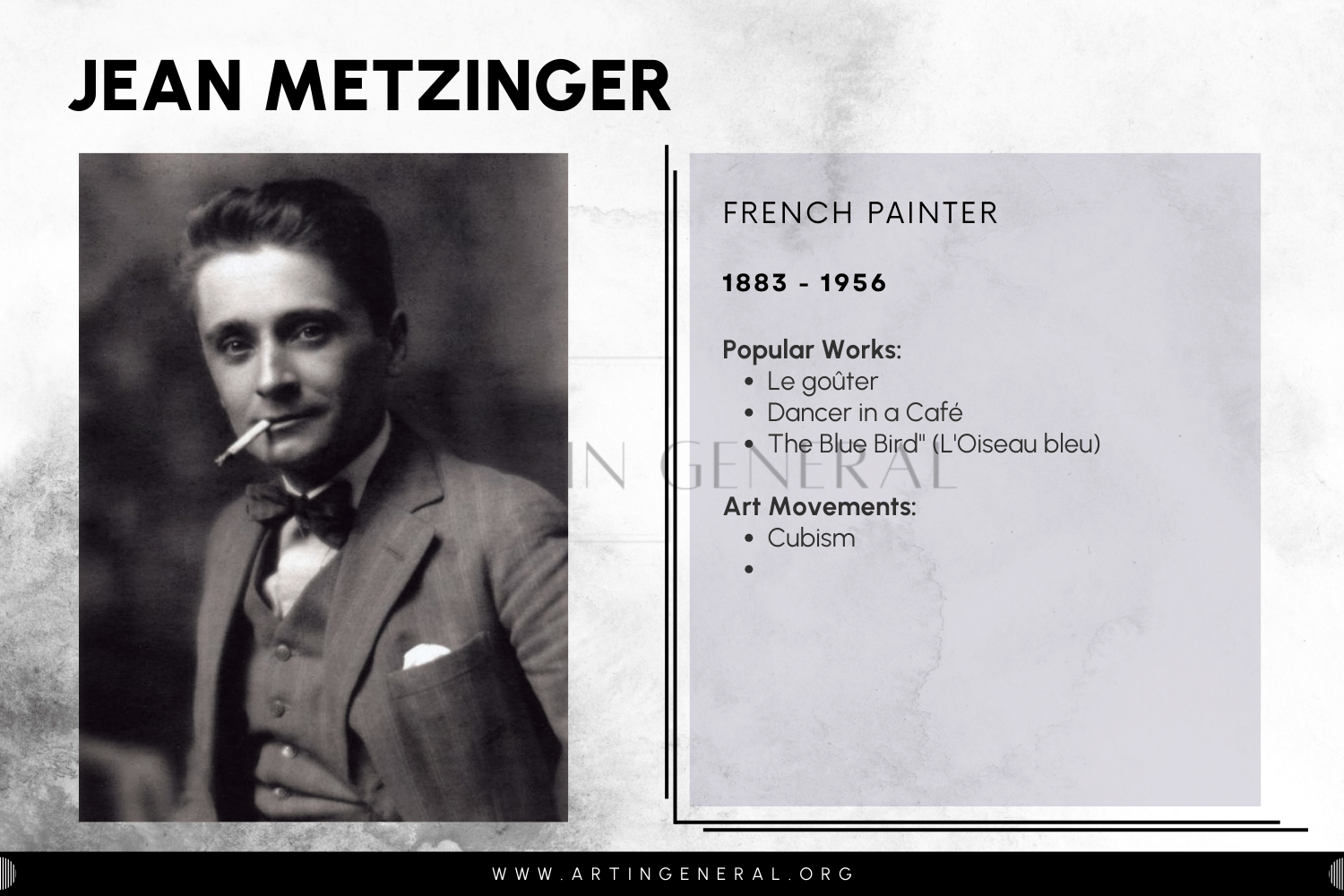

Jean Metzinger

Jean Metzinger resided in Paris throughout the formative years of his cubist movement. In contrast to Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, Metzinger was a prominent member of Salon Cubism.

Thanks to his theoretical education, Metzinger approached his painting with a more structured method. In particular, he applied faceting, geometry, and numerous views. His geometric forms, especially during his Crystal Cubist phase when he reduced form to a purity of geometric shape without completely straying into abstraction, made mathematics the focal point of his work.

Before 1912, Jean Metzinger concentrated on form; from around that time, he started emphasizing color equally. He created overlapping and intersecting surfaces and advanced the purity of abstract shapes during his Crystal Cubist period. Some major works by Jean Metzinger include At the Cycle-Race Track (1912), Le Goûter (1911), and Soldier at a Game of Chess (1914-5).

Albert Gleizes

French artist Albert Gleixzes created his paintings with the same mathematical precision that Metzinger applied to Cubism, focusing more on form than color in most of his creations. He used overlapping and intersecting shapes to give his images a dynamic quality that was evocative of a lot of Picasso’s cubism. Contrarily to Picasso, Gleizes’s work was more logically organized.

Cubism, in Gleizes’ words, was a “normal evolution of an art that was mobile like life itself.” Gleizes’ objective, in contrast to that of Picasso and Braque, was not the analysis and description of visual reality. Gleizes maintained that we can only know our experiences and not the outside world. His intricate, romantic conceptions of the physical world were not satisfied by commonplace items like a bowl of fruit, a guitar, or a pipe. His subjects have broad appeal as well as thought-provoking social and cultural implications. Some major works by Albert Gleizes include The Bathers (1914), Woman with Animals (1914), Woman with Phlox (1910), Woman with Black Glove (1920), and Composition for “Jazz” (1915).

Who were the key figures in the Cubism art movement, and what were their contributions?

The two main figures of the Cubism art movement were Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. They blended different perspectives on the same subject, typically objects or persons, to produce paintings that have an abstract, fractured appearance.

Masterpieces of Cubism

Some of the major artworks associated with Cubism include Les Desmoiselles d’Avignon (1907), Guernica (1937), Cubist Self-Portrait (1923), and The Weeping Woman (1937).

Les Desmoiselles d’Avignon

Artist: Pablo Picasso

Year: 1907

Medium: Oil on canvas

Location: Museum of Modern Art, New York City.

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon is a painting that radically departs from conventional perspective and composition. Three of the women give the viewer a blank, possibly hostile stare. Picasso nullifies any psychological interpretation of these women’s facial characteristics, leaving only the vague, menacing appearance of the figures.

Micronesian art is reflected in the figure on the far left, whose features may be associated with the inhabitants of an island in the South Seas of the Pacific. The heads of the two individuals directly to her right display Iberian sculpture forms and Picasso’s early influences from primitivism. In contrast to the pink tones of their bodies, the heads of the two figures on the right are clearly allusions to the shapes of African masks.

The sharp angles of the drapery, the facial features, and the uplifted arms create an overall impression that startles the viewer. Furthermore, the inconsistencies in the depictions of the corresponding faces from various cultures and the dehumanization of the stylized figures—which is debatable—are noteworthy. The cubist qualities of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon consist of its jagged and fragmented forms, sharp angularity, and ambiguous perspective.

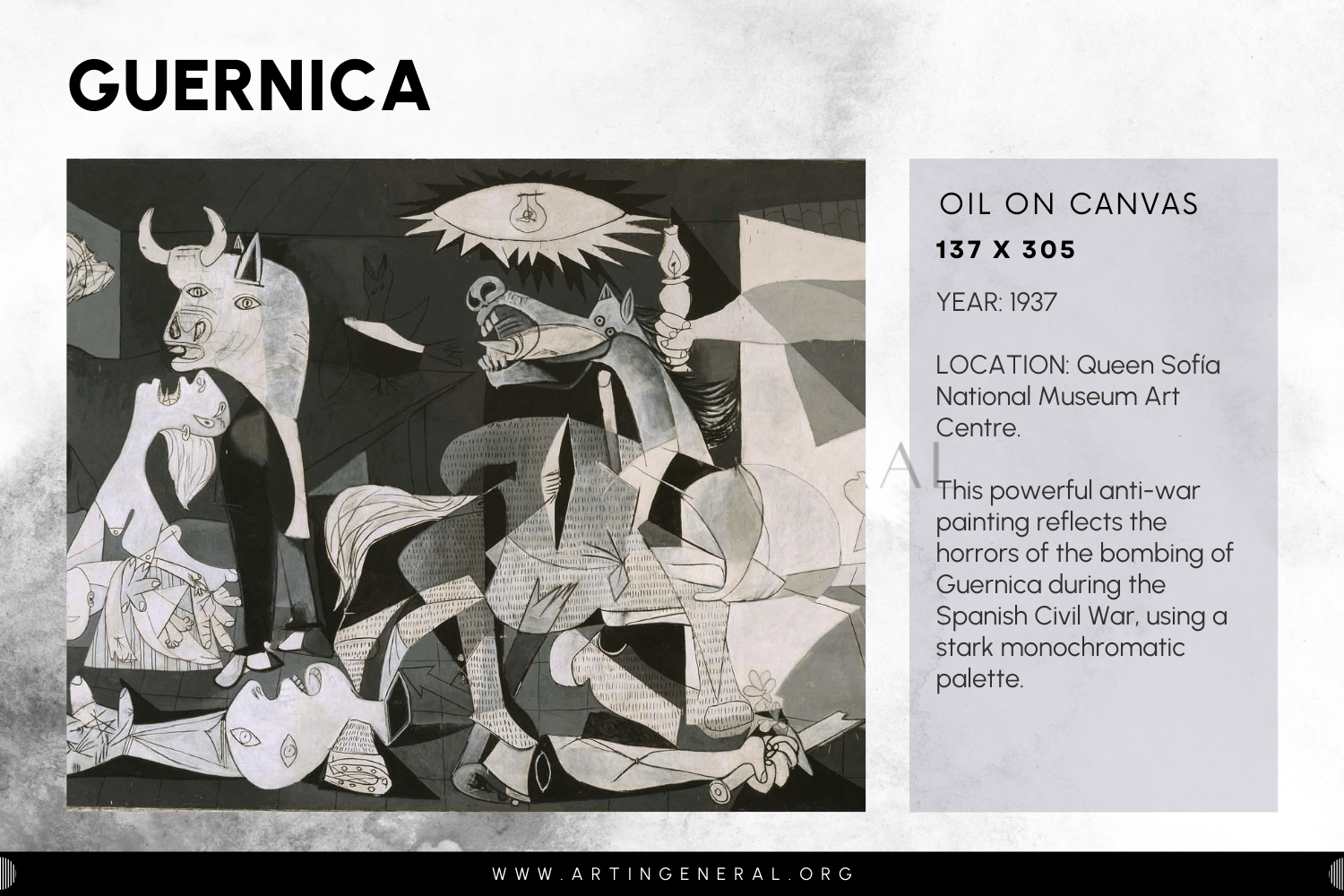

Guernica

Artist: Pablo Picasso

Year: 1937

Medium: Oil on canvas

Location: Museo Reina Sofía, Madrid, Spain.

Pablo Picasso’s Guernica explores the death and anguish associated with conflict. It was painted in response to the German and Italian bombing of the Spanish city of Guernica in April 1937, which was carried out at the Spanish nationalists’ instigation during the nation’s civil war.

In Guernica, a cramped, small place is depicted as being as unavoidable as the suffering brought on by violence. The painting’s lone glimmer of hope may be found in the wounded and mutilated soldier lying on his back in the left foreground, his severed arm clutching a broken sword from which a flower sprouts. A bull, which could be considered Spain’s national symbol, faces left and peers out onto what appears to be a barren countryside. Its tail’s dual function as smoke suggests that the nation torn apart by civil conflict is not doing well. The artwork features a troubled horse, a grieving mother carrying her deceased child in her arms, a woman’s possessed head peering through the window to the right, possibly representing the painter or the audience, and a woman on the far right, with her arms extended and engulfed in stylized flames shaped like knives. A bald lightbulb shaped like an eye is located overhead, symbolizing either God’s helplessness or complacency in the face of such suffering.

Cubist forms of fractured surfaces and shapes are a fitting way to depict a topic like this, which suggests social alienation and bodily mutilation. The most intricate and analytically Cubist phase in the image is where there is a flurry of writhing limbs and forms in the center. The overlapping shapes of the soldier and horse allude to bodily harm and disorientation.

Nevertheless, the image as a whole is not affected by its rich Cubism. Picasso uses a more visually cohesive figuration on either side of the focal passage. He counterbalances the piece’s fractures and distortions with a sketch that depicts the situation more accurately and evokes sympathy and shock. This painting is characterized as overwhelming by the combination of Cubist forms, the unnatural deformities and anguish, and the evocative monochrome color scheme. The picture’s Cubism may contribute to its psychological realism in addition to its visual realism.

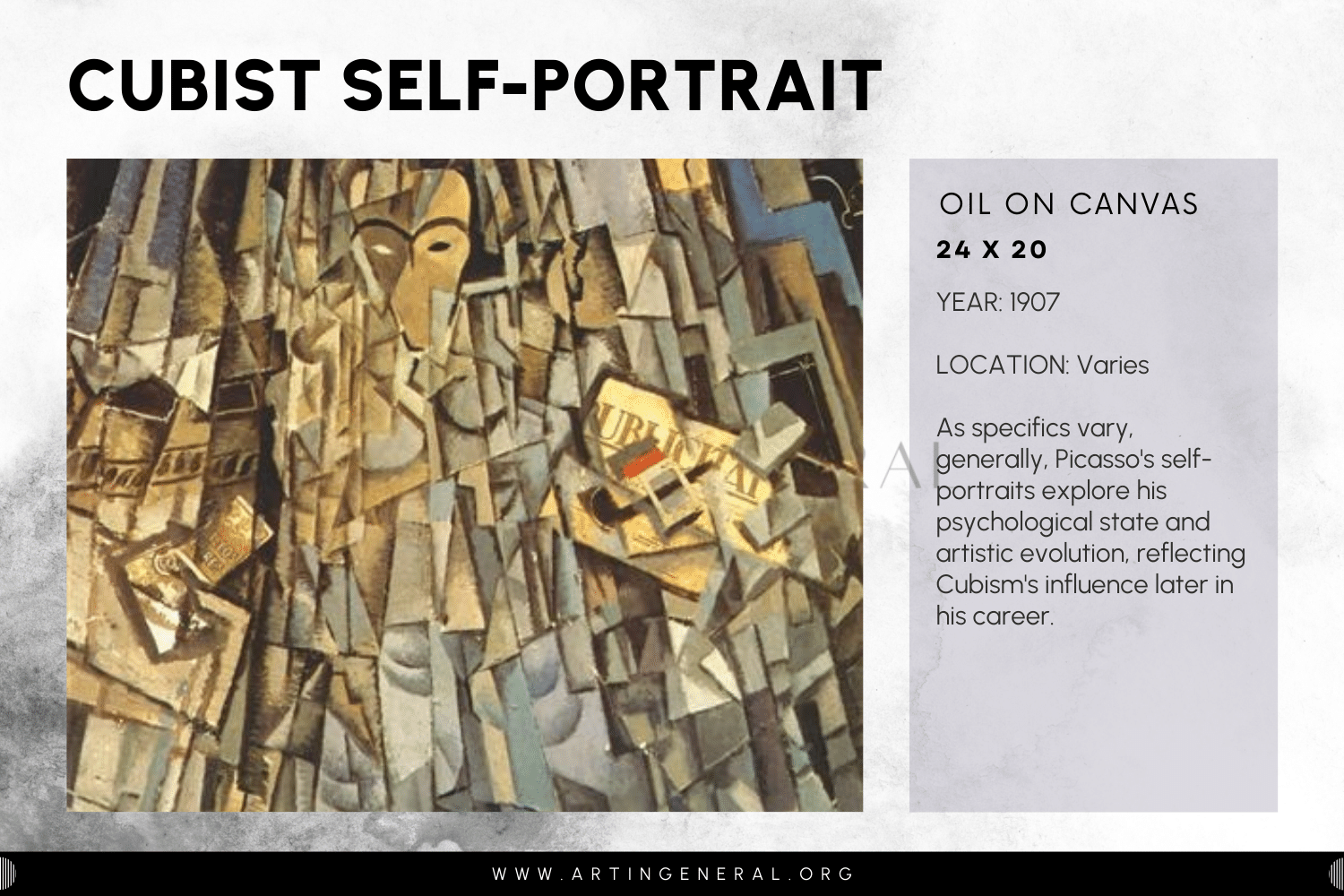

Cubist Self-Portrait

Artist: Salvador Dali

Year: 1923

Medium: oil and collage on paperboard glued to wood

Location: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Spain

Salvador Dalí’s Cubist Self-Portrait depicts the artist’s apparently disembodied head with its stark angularity and pronounced eyebrows. The absence of a mouth on the head suggests silent observation, possibly a self-aware nod to his recent research and experimentation with Cubism. The convex structure that curves outward toward the painting’s foot and goes down the middle of the composition gently suggests the figure’s body.

The image exhibits cubist characteristics, such as the fragmented yet orderly composition of the structures, which resembles a succession of glassy fragments. This is reminiscent of Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque’s analytic period a decade and a half earlier. However, Dalí is also employing the synthetic Cubism collage approach in this instance. That means that the piece could be classified as a synoptic merging of the two canonical stages of Cubism. Hence, employing formal and technical methods instead of narrative construction, the image serves as a visual chronicle of the artistic evolution of Cubism. Furthermore, the artist’s basic likeness firmly situates him within this prestigious and illustrious avant-garde movement.

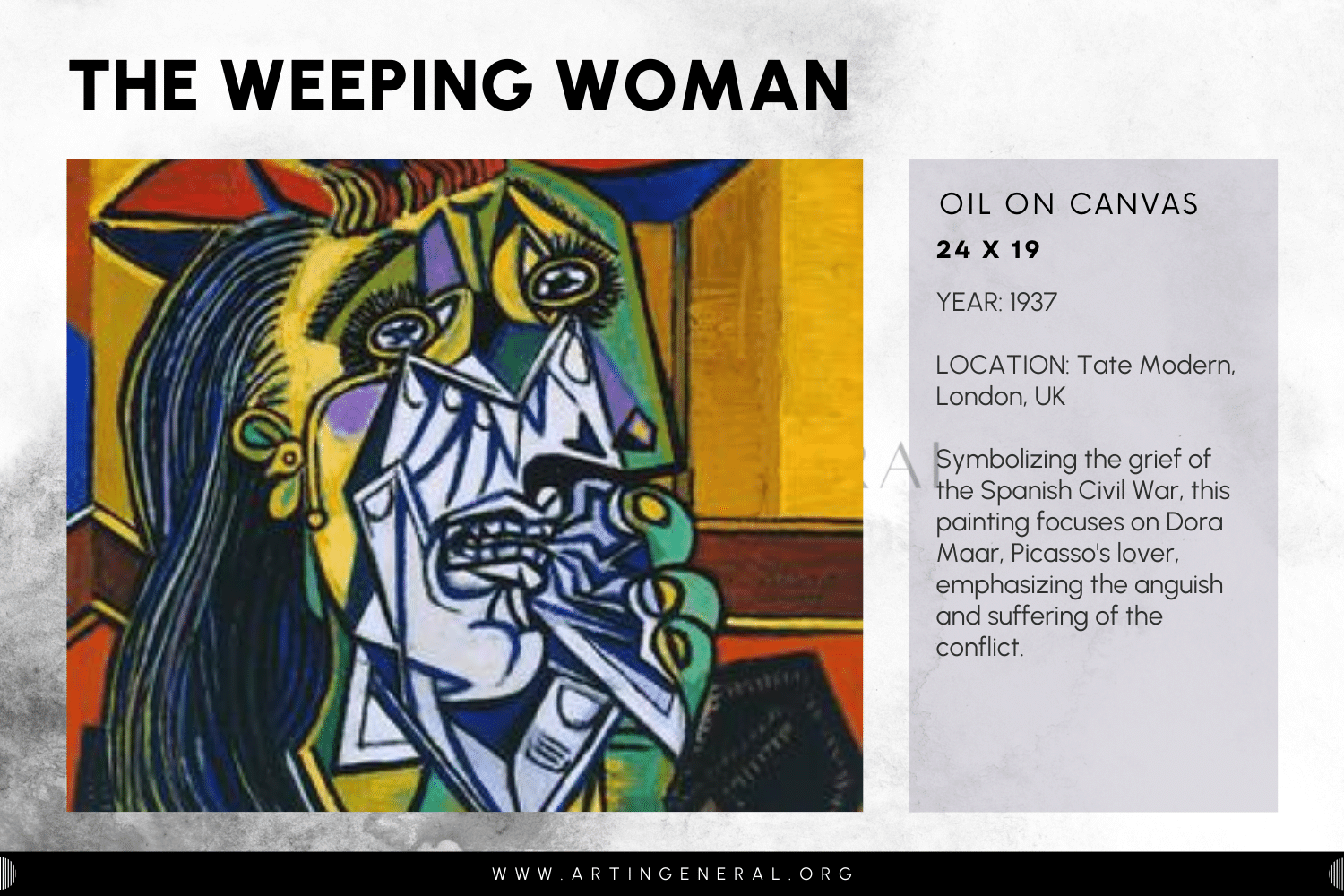

The Weeping Woman

Artist: Pablo Picasso

Year: 1937

Medium: Oil on canvas

Location: Tate Modern, London

In The Weeping Woman, a bereaved woman is shown in miniature with her handkerchief held up to her face. The portrait is an extremely distorted representation of Picasso’s partner and muse at the time, the Surrealist photographer Dora Maar. The sobbing figure can allude to either Maar’s frequently mentioned melancholy disposition or the violent relationship between the two artists.

Rather than being overtly Cubist, the painting is more normally organized. Cubist features include the odd angle of the wall paneling in the left backdrop and the sitter’s attire, which also depicts such times with details like the wrinkles on the figure’s shoulders. These are used to great effect, and the woman is shown with characteristic Cubist faceting and “moving” contours. Moreover, the intricate and pointed geometry of the handkerchief and the apparent facial mobility suggested by the nose’s erratic posture are distinctly Cubist.

What are the most iconic Cubism artworks and why are they significant?

The early Cubist movement is exemplified by Les Desmoiselles d’Avignon (1907), which features geometric abstraction, fractured forms, and numerous perspectives. The idea of classical beauty was destroyed by this painting, opening the door for the Cubist movement.

Remarkably, Still Life with Chair Caning (1912) is among the earliest collage pieces in fine art. Picasso blurred the lines between painting and sculpture and increased the range of artistic expression by including a piece of oilcloth printed with a chair caning pattern in the picture. This creative use of collage questioned traditional ideas of representation and materials in art.

Cubism vs. Fauvism

Fauvism and Cubism flourished in Paris during the first decade of the twentieth century. The subjects are similar in that they are both still lifes with fruits and other everyday things. Neither are accurate depictions of their subjects; instead, they are highly romanticized versions of them. Both don’t limit themselves to the actual colors of the still life, instead using a striking color scheme. Above all, both works experiment with the standard practices of life drawing, drawing influence from various color or shape representations.

Cubism emphasizes the canvas’s two-dimensionality and attempts to depict objects using geometric shapes in a small area. Conversely, Fauvism emphasizes the feelings an object evokes in the artist rather than the object’s actual existence. It makes use of solid and unconventional colors and crude brushwork. It de-emphasizes object shape to produce an eye-catching and pleasing piece. Fauvism also has straightforward expression and softened edges.

Cubism vs. Realism

Realism is a Western art movement that began in France in 1840 and continued into the late 1800s. Cubism employed formal and perspectival experiments to accomplish the fragmented composition—French realism aimed to depict scenes from daily life as accurately and simply as possible. The representation of socioeconomic classes and abstraction are two more distinctions. The similarities include using a limited color palette, rejecting acceptable art conventions, and the faithful depiction of reality.

Cubism vs. Impressionism

The French Impressionist painting movement began in the mid- to late-19th century, roughly between 1874 and 1886. Little, noticeable brushstrokes that provide a crucial impression of form, pure color, and a focus on faithfully capturing natural light are characteristics of Impressionist painting. The primary distinctions from Cubism pertain to the subject matter, color scheme, and incorporation of time.

Three major similarities exist between Impressionism and Cubism: they both reject the rigid conventions of academic painting, use constructively fractured brushwork, and are representational.

Cubism vs. Surrealism

The 1910s saw the rise of surrealism, which became formally recognized in 1924 and persisted through World War II. The similarities between surrealism and cubism are numerous, even though they might not be immediately apparent. Three things link surrealism and cubism: they have two main stylistic periods, imagine new or other realities, and have an abstracting tendency. Three things set surrealism apart from cubism: illusionism, influences, and the fact that surrealism was a cultural movement.

How did Cubism pave the way for Futurism?

Futurism was initiated around 1910 by the Italian Futurists. The dynamism of the machine served as an inspiration for the Futurists, who rebelled against the cubist analysis of static form by elevating and emphasizing it in their creative vision. Their main concern was simulating movement by applying layers and blurring to provide the appearance of dynamic movement.

What other art movements were inspired by or related to Cubism?

This particular manifestation of cubism established a precedent for non-representational art through its novel emphasis on the harmony between the subject matter and the canvas. It cleared the path for later avant-garde movements, such as De Stijl, Dadaism, Constructivism, Surrealism, and Futurism.

How does Cubism continue to influence modern art and culture?

Cubist approaches inspire modern artists, who reimagine fractured forms and embrace numerous angles of view. Cubism continues to influence artists today, from sculptors to painters, continually changing and adapting to the new reality.

Leave a Reply