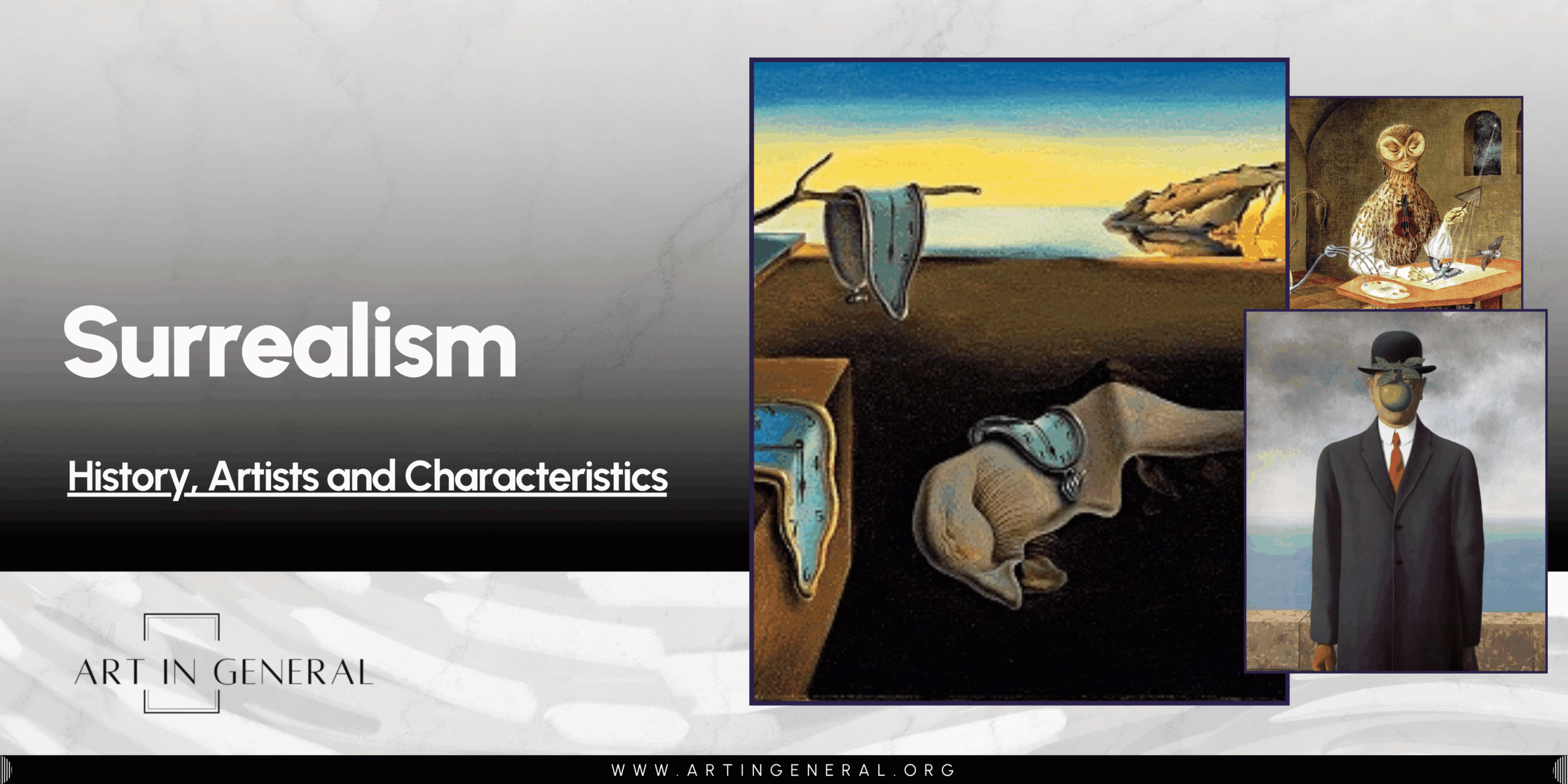

Surrealism is an art movement that sought to unlock the hidden depths of the human mind. Emerging in the early 1920s, it rejected rational thought and embraced the strange, the dreamlike, and the unexpected. Surrealist artists believed that creativity was most powerful when it flowed directly from the subconscious, and behaved like the subconscious: unfiltered, unrestrained, and free from the conventions of society.

Guided by the ideas of psychoanalysis and the trauma of a post-war world, Surrealism became both a rebellion and an exploration. Its paintings often feature uncanny landscapes, impossible combinations of objects, and scenes that feel as familiar as they are unsettling, much like the logic of dreams. While the movement began in literature, it flourished most vividly through visual art, with painters, sculptors, and photographers reinventing how reality could be portrayed.

From Salvador Dalí’s melting clocks to René Magritte’s quiet paradoxes, Surrealism continues to fascinate viewers today. It invites us to look deeper, question what we see, and consider the mysteries of our own inner world.

Origins of the Surrealist Movement

A Post-War World in Search of Meaning

Surrealism was born in the aftermath of World War I, a conflict that left Europe devastated and disillusioned. Traditional beliefs like political, moral, and artistic values had been shaken. For many writers and artists, the rational world no longer made sense. This climate of doubt and upheaval paved the way for a new kind of artistic expression.

Before Surrealism fully emerged, many of its early members were involved in Dada, an anti-art movement that rejected logic, order, and conventional values. Dada celebrated absurdity and chaos, but its spirit was rooted in protest. As the 1920s began, some artists felt an urge to move beyond destruction and toward creation. They wanted to channel the same freedom and rebellion into something more structured and visionary.

This desire to rebuild from the ruins of reason gave birth to Surrealism.

The Literary Foundations

Surrealism first took shape in the world of literature. The French poet André Breton, influenced by Sigmund Freud’s theories on dreams and the subconscious, believed that true creativity came from releasing the mind’s deepest and most hidden thoughts. Together with writers like Louis Aragon, Philippe Soupault, and Paul Éluard, Breton began experimenting with automatic writing, a technique meant to bypass conscious control.

In 1924, Breton published the Surrealist Manifesto, formally defining Surrealism as “pure psychic automatism.” The manifesto called for an art that encouraged “the dictation of thought” without censorship or rational interference. It quickly united a growing circle of poets, painters, and thinkers who shared his vision.

Surrealism Becomes an Art Movement

What began as a literary experiment soon expanded into the visual arts. Paris became the center of Surrealist activity, attracting painters, sculptors, and photographers from across Europe. Max Ernst introduced collage techniques and invented frottage; Joan Miró explored biomorphic abstraction; René Magritte developed his quiet, philosophical illusions; and Salvador Dalí’s arrival in 1929 infused the movement with theatricality and precision.

Early Surrealist exhibitions showcased works filled with dreamlike imagery, bizarre juxtapositions, and psychological symbolism. The movement quickly spread beyond France, influencing artists in Belgium, Spain, Germany, the United States, and Mexico, where Surrealism found a natural connection with local mythology and spirituality.

By the early 1930s, Surrealism had become one of the most influential cultural forces of the 20th century. It reshaped not only painting and sculpture but also poetry, film, photography, and design, leaving a legacy that still echoes in contemporary culture today.

Characteristics of Surrealist Art

Surrealist art is instantly recognizable for its ability to merge the ordinary with the extraordinary. These works live in a space where dreams and waking reality blend, where logic dissolves, and where imagination is granted full authority. While the movement embraced many different styles, surrealist artists shared a common desire: to reveal the hidden workings of the human mind. Below are the defining traits that shaped Surrealism and gave the movement its unmistakable visual identity.

Dreamlike Imagery

Surrealist paintings often resemble scenes pulled directly from a dream. Everyday objects appear in impossible settings, figures float weightlessly, and landscapes twist into uncanny forms. The familiar becomes strange, and the strange becomes familiar. This dream-logic invites viewers to step inside a world governed not by reality, but by emotion, memory, and the subconscious.

Automatism

At the heart of early Surrealism was automatism, which practically speaking was the belief that true creativity emerges when the conscious mind is bypassed. By allowing the hand to move freely across the page, artists like André Masson and Joan Miró created forms that seemed spontaneous and organic. These marks often became the starting points for larger compositions, where instinct guided the imagery more than deliberate planning.

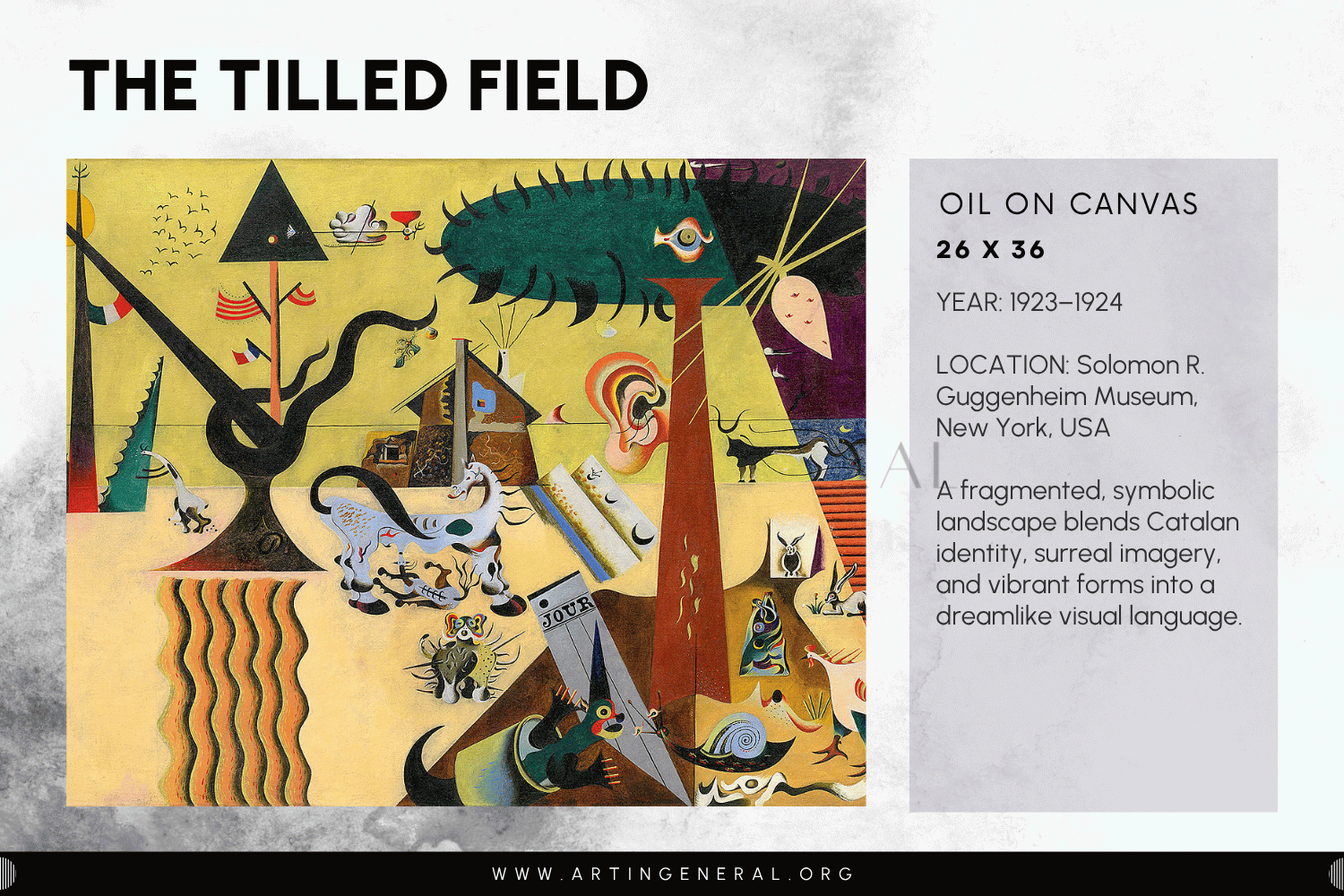

“The Tilled Field” by Joan Miró

The Tilled Field marks a turning point in Miró’s career, bridging his early representational style with the Surrealist vocabulary he would later develop. At first glance, the painting depicts a rural Catalan landscape, but upon closer inspection, the scene dissolves into a tapestry of symbols, abstract forms, and whimsical distortions. Animals, plants, and human features appear throughout, each rendered with playful exaggeration and rhythmic lines.

Miró blends personal memory with subconscious invention, creating a landscape that feels alive with coded messages. The imagery reflects a deep connection to Catalan identity, yet it transcends the literal through its fantastical elements. Objects seem suspended in space or flattened into decorative shapes, foreshadowing the biomorphic language that would define his later work. This painting stands as an early example of how Surrealism could emerge not from shock or absurdity alone, but from the reinvention of familiar subjects. The Tilled Field transforms a simple pastoral scene into a dreamscape pulsing with energy, symbolism, and imaginative possibility.

Unexpected Juxtaposition

One of Surrealism’s most powerful strategies is the placement of unrelated objects together in a single scene. This technique was rooted in a line by poet Lautréamont that produces images that feel simultaneously rational and impossible. It can be playful, unsettling, or even poetic. René Magritte mastered this approach with works that challenge the viewer’s expectations and reveal the fragile nature of perception.

Metamorphosis and Transformation

Surrealist artists often depicted objects undergoing slow, fluid transformations. Figures melt, stretch, dissolve, or morph into something entirely new. Salvador Dalí’s paintings, with their soft clocks and elongated shadows, epitomize this fascination with shifting identities and unstable forms. These transformations symbolize the constant evolution of the psyche and the instability of the external world.

Hyperrealism vs. Abstraction

Surrealism isn’t limited to a single visual language.

Some artists, such as Dalí, Magritte, and Yves Tanguy, used hyperrealist precision to paint impossible scenes with photographic clarity. Their attention to detail heightens the strangeness of their imagery. Others, like Miró and Masson, moved toward abstraction, using biomorphic shapes and intuitive lines to convey emotions and subconscious impulses. These two approaches coexist within the movement, showcasing the vast creative freedom that Surrealism embraced.

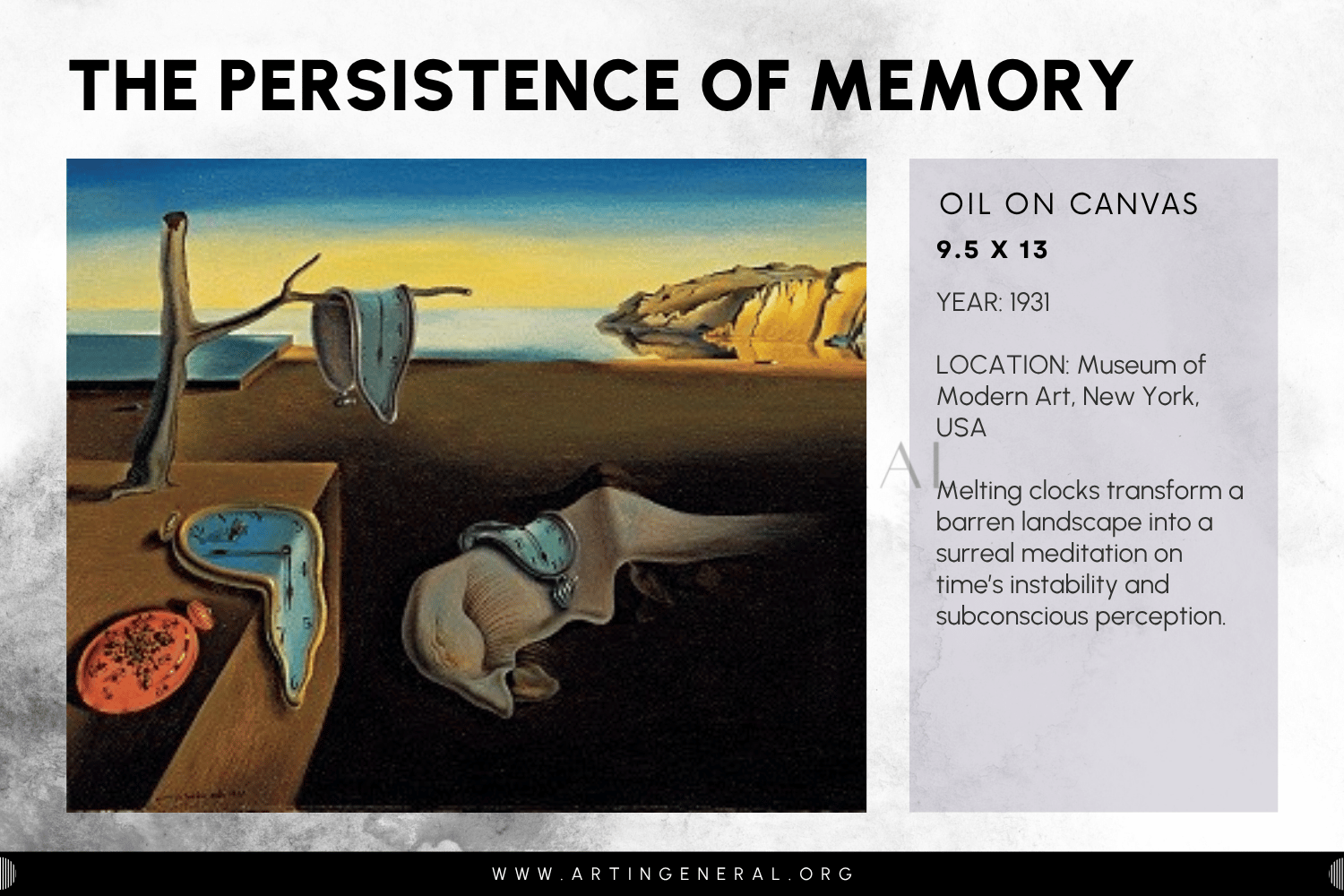

“The Persisitence of Memory” by Salvador Dalí

Dalí’s The Persistence of Memory is one of the most recognizable artworks in modern art, yet its meaning remains slippery and elusive, just as the Surrealists intended. Painted with impeccable precision, the work presents a barren, dreamlike landscape populated by melting clocks draped over branches, ledges, and what appears to be a distorted self-portrait lying on the ground. The hyperreal rendering contrasts sharply with the irrationality of the scene, intensifying its uncanny effect.

Time, one of the most rigid constructs of the rational world, becomes soft and unstable, suggesting the fluidity of memory and the unreliability of human perception. The quiet, desolate setting which was often compared to Dalí’s native Catalonia adds a haunting stillness, while the distant horizon creates a sense of infinite space. The painting is neither a direct narrative nor a puzzle with a single solution, but rather an invitation to meditate on the way time and consciousness distort one another. Its enduring power lies in how familiar and strange it feels at once.

Psychological and Symbolic Themes

Surrealist works often explore subjects that lie beneath the surface of consciousness: desire, anxiety, memory, violence, sexuality, and identity. Many artists drew from mythology, folklore, dreams, and personal symbolism to construct their imagery. These themes give Surrealism its depth and emotional resonance, encouraging viewers to reflect on their own inner worlds.

Which Painting Techniques Were Used in Surrealist Painting?

Surrealism’s innovative spirit extended beyond subject matter to include experimental techniques designed to free creativity from traditional constraints. These methods encouraged spontaneity, accident, and discovery, the key principles for artists seeking to express the subconscious mind.

- Frottage: Developed by Max Ernst, frottage involves placing paper over textured surfaces and rubbing it with graphite or charcoal. The resulting patterns served as starting points for imaginative compositions, revealing shapes and forms that seemed to emerge naturally from the material.

- Grattage: A related technique, grattage, required scraping away layers of wet paint from a canvas to reveal underlying textures. This method produced organic, unpredictable shapes that artists could develop into fantastical imagery.

- Decalcomania: This method involved pressing paper or glass onto a painted surface and then lifting it to create branching, veined forms. These intricate patterns inspired landscapes, creatures, and abstract scenes, particularly in the works of Óscar Domínguez and Max Ernst.

- Collage and Photomontage: Collage played a central role in expanding Surrealist visual language. Artists combined newspaper clippings, photographs, advertisements, and unrelated materials to create startling compositions. Photographers like Man Ray and Dora Maar experimented with montage, solarization, and darkroom manipulation to push the boundaries of what an image could express.

- Automatic Drawing and Painting: Through rapid mark-making and free-flowing brushstrokes, artists attempted to create without conscious control. Automatic drawing became a foundation for many Surrealist compositions, allowing unexpected forms to emerge. Miró’s early works are key examples of this practice, blending spontaneity with precision and later refinement.

- Hyperrealist Technique: Not all Surrealists favored loose or experimental methods. Artists like Dalí and Magritte used meticulous, academically trained techniques to paint impossible scenes with convincing realism. This clarity made their dreamlike imagery even more striking, as the viewer is confronted with something visually believable yet logically impossible.

Key Surrealist Artists

Surrealism brought together a remarkably diverse group of painters, sculptors, poets, and photographers, each contributing a unique interpretation of the subconscious mind. While united by their desire to break free from rational constraints, their approaches ranged from meticulous realism to fluid abstraction. Below are some of the most influential figures whose work defined and expanded the Surrealist movement.

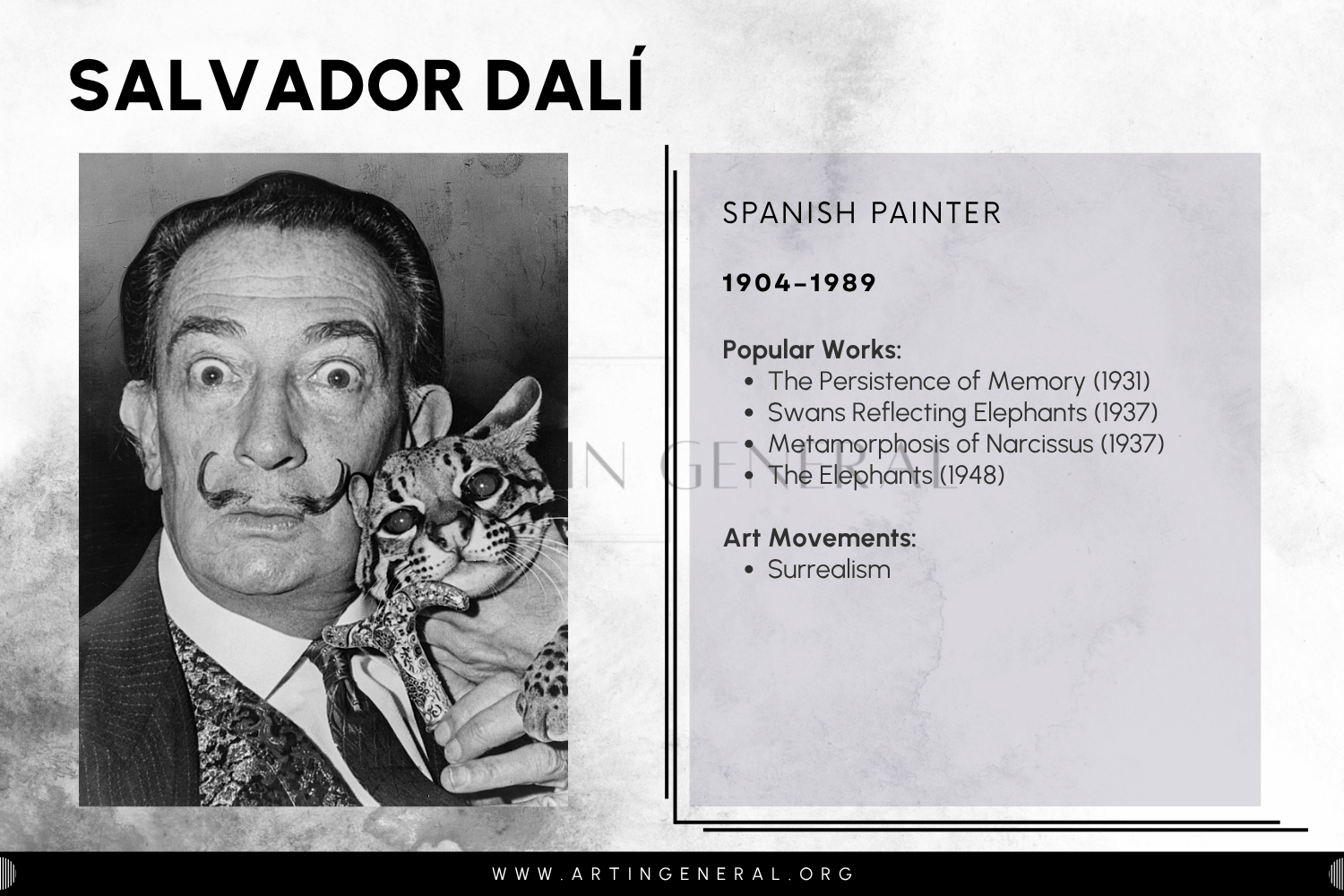

Salvador Dalí (1904–1989)

Salvador Dalí remains the most widely recognized Surrealist, celebrated for his extraordinary imagination and technical precision. Born in Catalonia, Dalí trained in academic realism, a skill he later used to give his dreamlike scenes a striking sense of clarity. His arrival in the Surrealist group in 1929 brought theatricality, symbolism, and psychological intensity to the movement.

Dalí explored themes of desire, time, memory, and decay, often incorporating melting forms, desert landscapes, and elongated shadows. His flamboyant personality and public performances further cemented his status as a central figure in Surrealism.

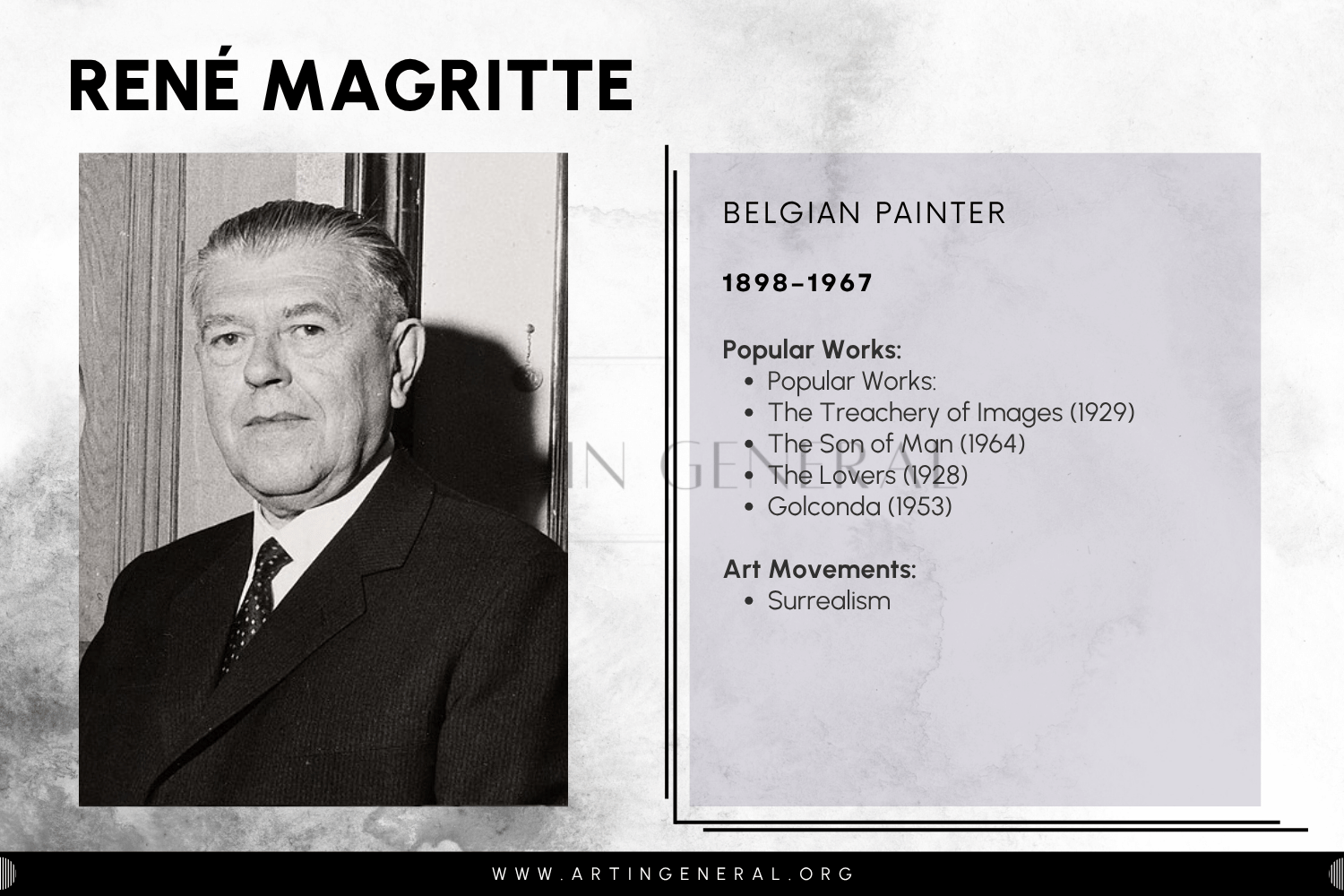

René Magritte (1898–1967)

René Magritte approached Surrealism with a distinctly philosophical lens. Rather than constructing fantastical dreamscapes, he used everyday objects like apples, pipes, bowler hats, and placed them in unusual or contradictory contexts. His work challenges viewers to reconsider the relationship between images and words, reality and representation.

Magritte’s quiet precision, paired with his enigmatic compositions, established a form of Surrealism rooted not in spectacle but in thought. His paintings are often described as visual puzzles that invite reflection rather than emotional release.

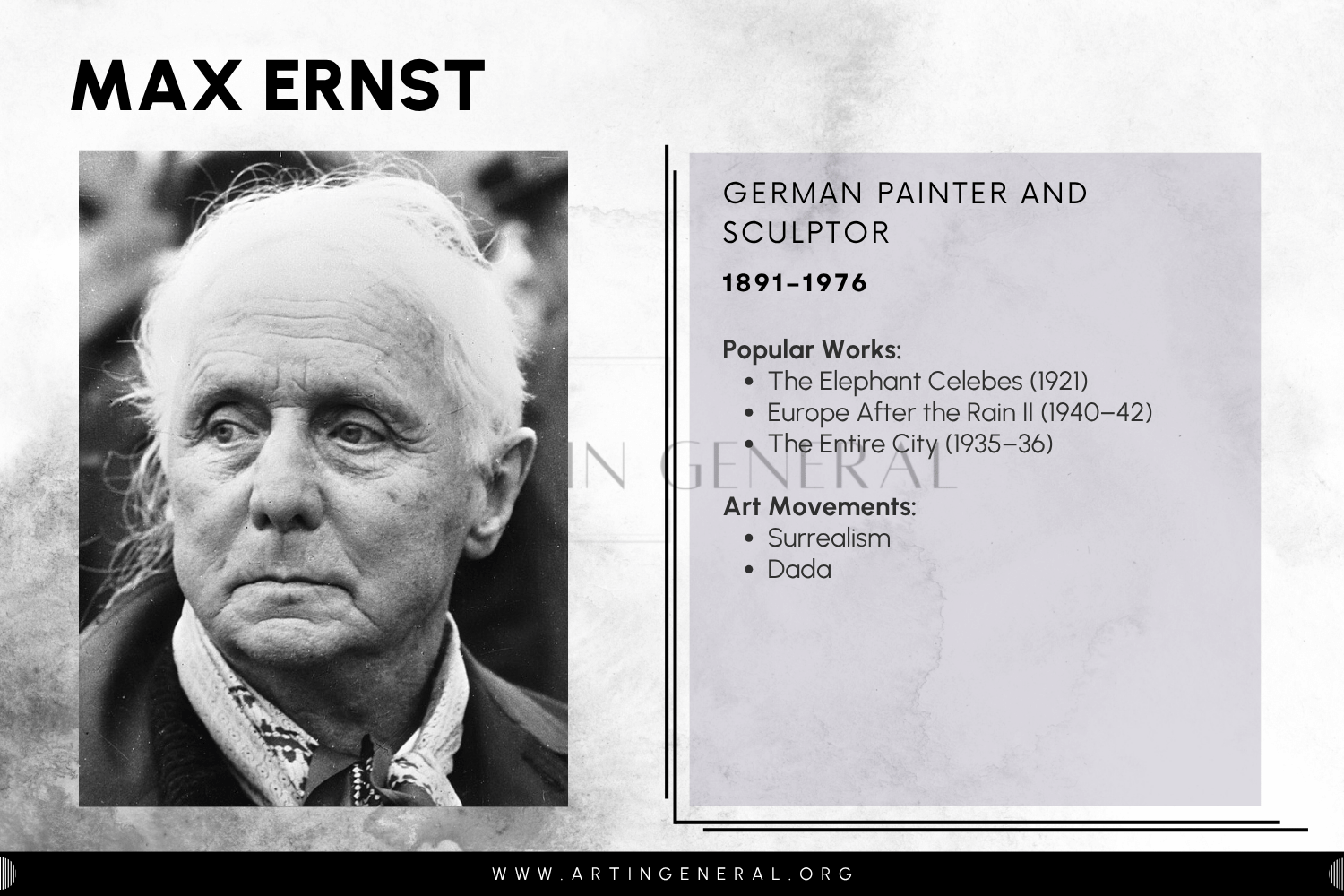

Max Ernst (1891–1976)

Max Ernst was a pioneer of Surrealist experimentation. Initially associated with Dada, he introduced techniques that expanded the possibilities of art-making, including frottage, grattage, and collage. His imagery often blends mechanical structures, forest motifs, and fantastical creatures, creating worlds that feel simultaneously ancient and futuristic.

Ernst’s innovative spirit helped shape the vocabulary of Surrealism and inspired many younger artists. His work embodies the movement’s commitment to spontaneity, chance, and psychological depth.

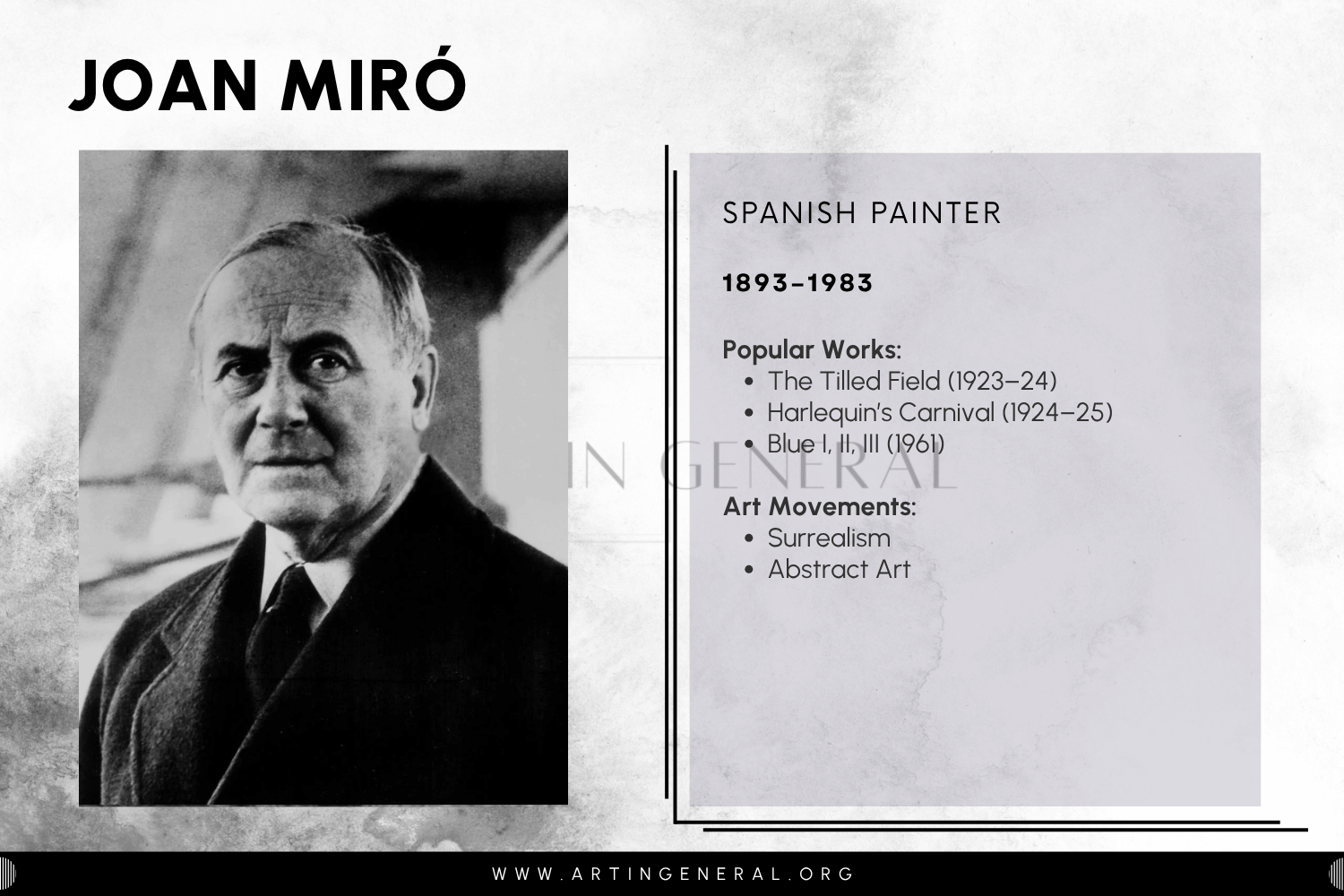

Joan Miró (1893–1983)

Joan Miró’s contribution to Surrealism stems from his em

brace of automatism and his development of a distinctive vocabulary of abstract, biomorphic shapes. His early works, rooted in Catalan culture and folk art, gradually transformed into compositions filled with floating forms, playful lines, and vivid colors.

brace of automatism and his development of a distinctive vocabulary of abstract, biomorphic shapes. His early works, rooted in Catalan culture and folk art, gradually transformed into compositions filled with floating forms, playful lines, and vivid colors.

Miró avoided direct symbolism, preferring spontaneous creation to conscious planning. His works feel alive with movement and rhythm, reflecting his belief in art as a bridge between the physical and subconscious worlds.

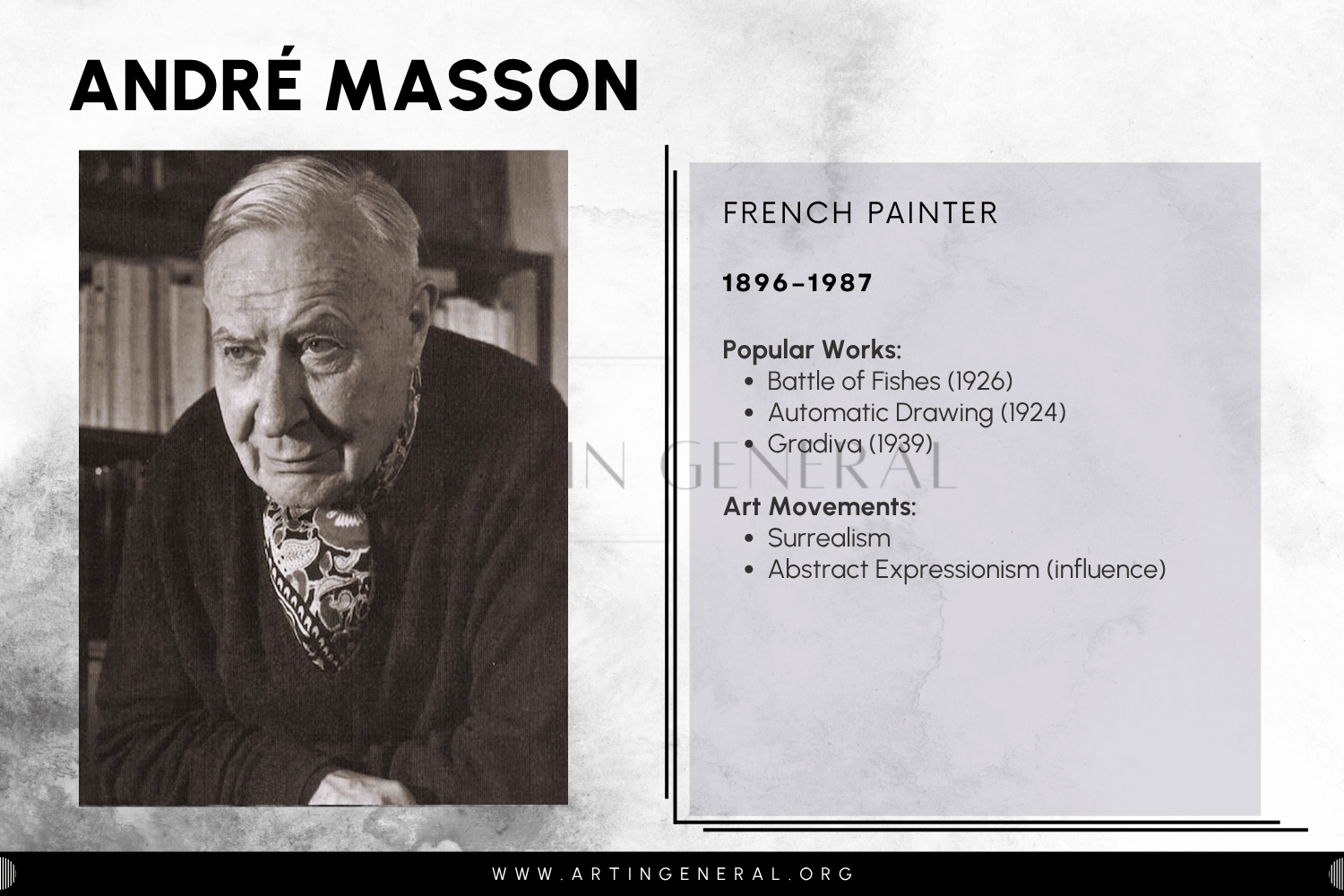

André Masson (1896–1987)

André Masson played a crucial role in the development of automatic drawing. His technique involved allowing the hand to move freely across the page, generating lines and forms that later evolved into finished compositions. Masson’s works often explore themes of violence, mythology, and eroticism, reflecting the raw and often contradictory impulses of the human psyche.

Masson was also instrumental in spreading Surrealist ideas to the United States during World War II, influencing a younger generation of artists, including pioneers of Abstract Expressionism.

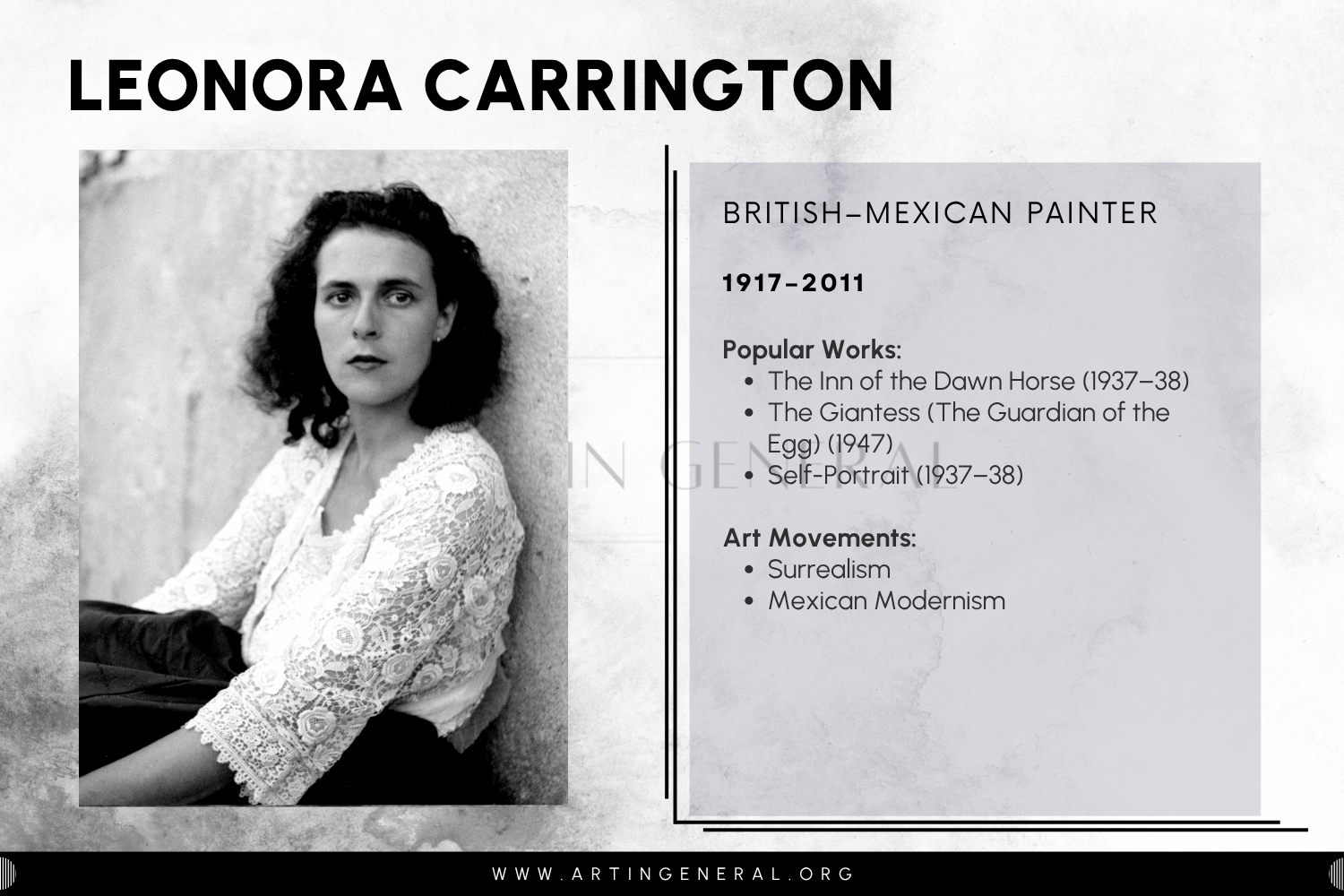

Leonora Carrington (1917–2011)

British–Mexican Painter

Leonora Carrington brought a mystical, feminist perspective to Surrealism. Born in England and later based in Mexico, she developed a deeply personal visual language rooted in magical realism, Celtic mythology, alchemy, and occult symbolism. Her paintings often feature powerful female figures, hybrid creatures, and dreamlike rituals.

Carrington’s work helped broaden the movement’s thematic range, emphasizing intuition, myth, and the interior world of women which were domains largely overlooked by her male contemporaries.

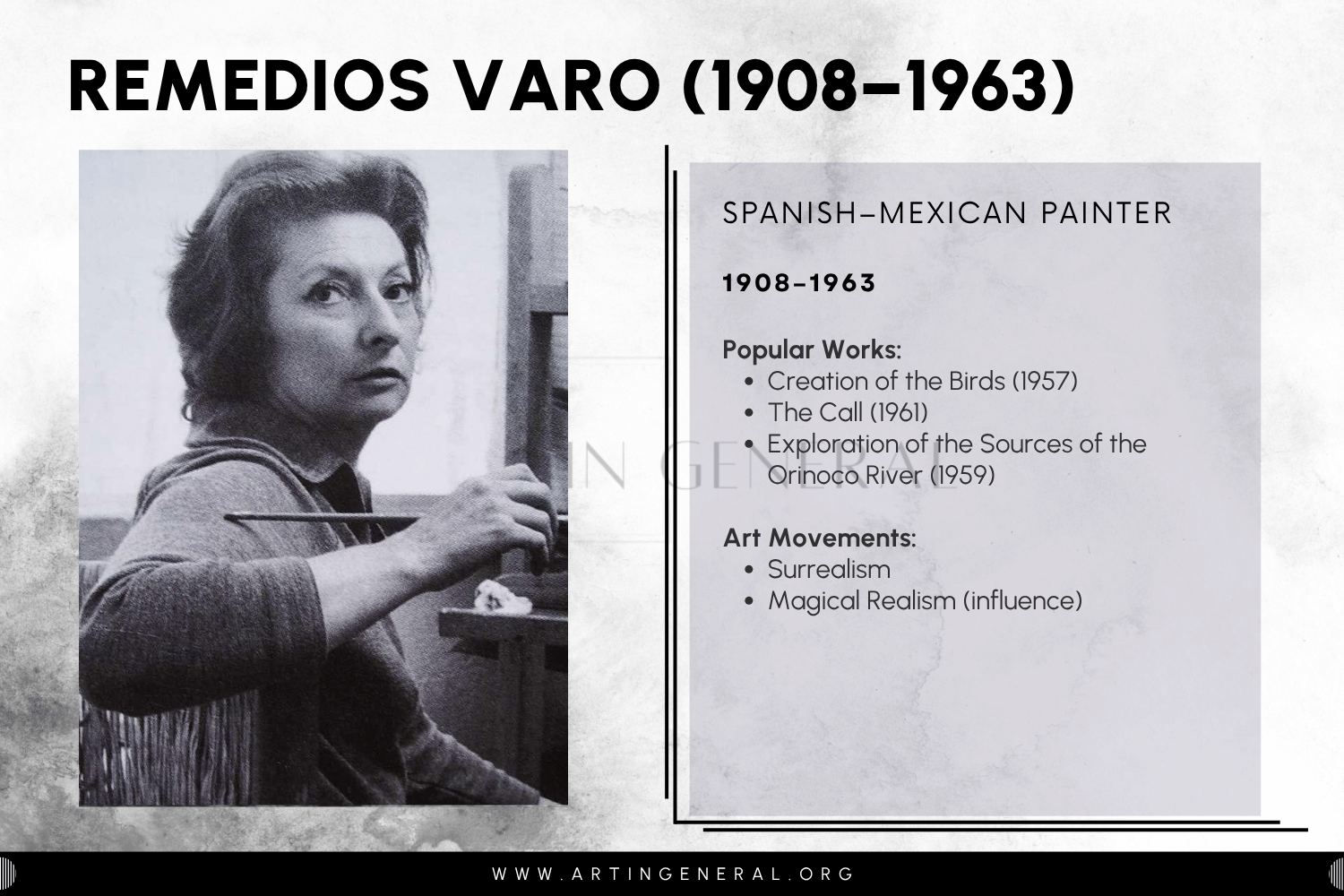

Remedios Varo (1908–1963)

A close contemporary of Carrington, Remedios Varo created intricately detailed scenes blending science, mysticism, and personal mythology. After fleeing the Spanish Civil War and World War II, she settled in Mexico City, where her work flourished.

Varo’s paintings often depict enigmatic figures engaged in alchemical experiments, spiritual journeys, or creative transformations. Her precise technique and narrative depth make her one of the most celebrated painters in Latin American Surrealism.

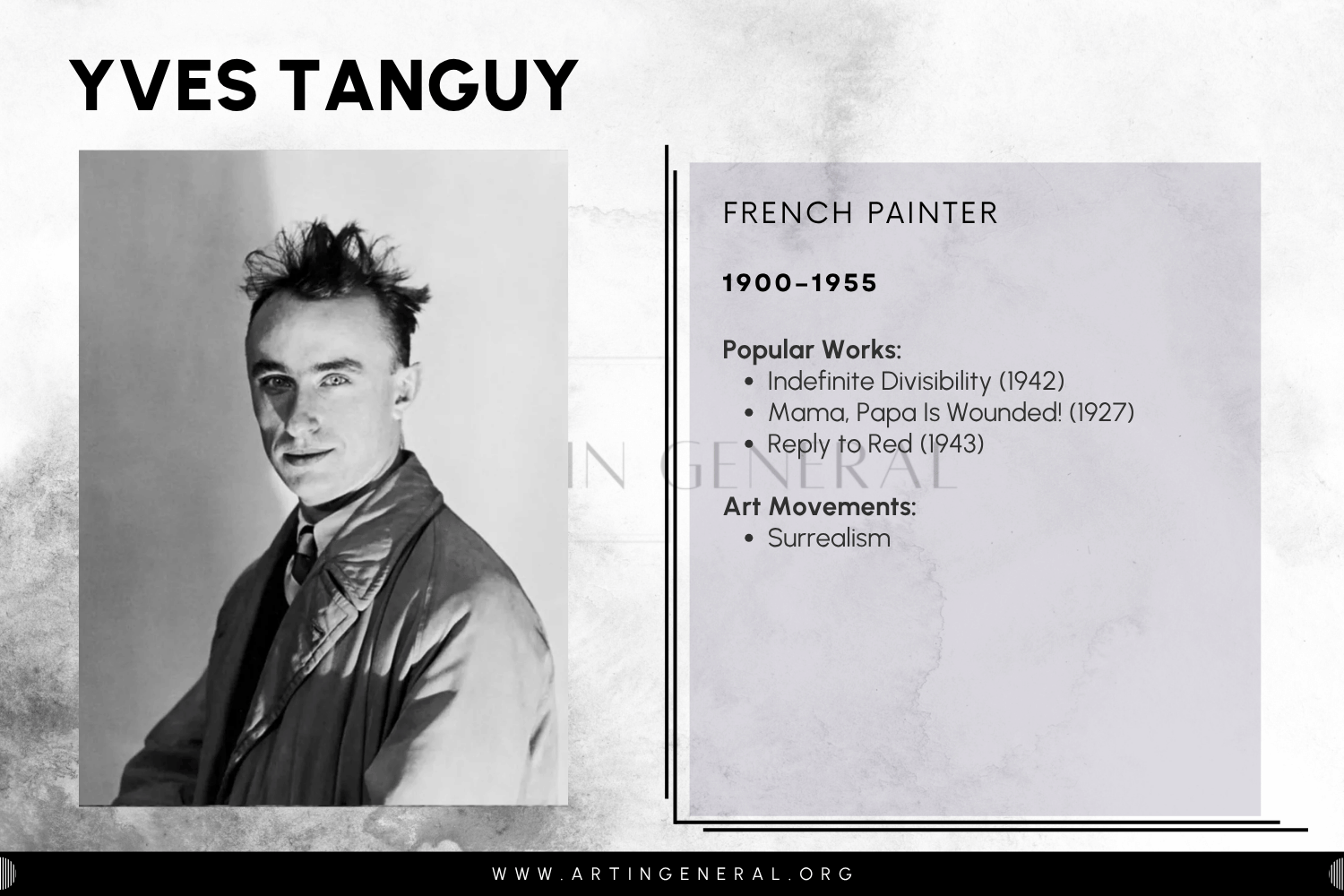

Yves Tanguy (1900–1955)

Yves Tanguy is best known for his vast, dreamlike landscapes populated by biomorphic stones, shadows, and ambiguous forms. His works are meticulously rendered yet almost entirely abstract, creating environments that feel otherworldly and timeless.

Tanguy’s ability to evoke psychological and emotional states through nonrepresentational forms made him a pivotal figure within Surrealism. His style later influenced American artists such as Arshile Gorky and Jackson Pollock.

Masterpieces of Surrealism

Surrealism produced some of the most iconic and thought-provoking images of the 20th century. These works challenge our expectations, distort reality, and invite viewers into the private landscape of dreams and the subconscious. Below are several key masterpieces that shaped the movement and continue to fascinate audiences worldwide.

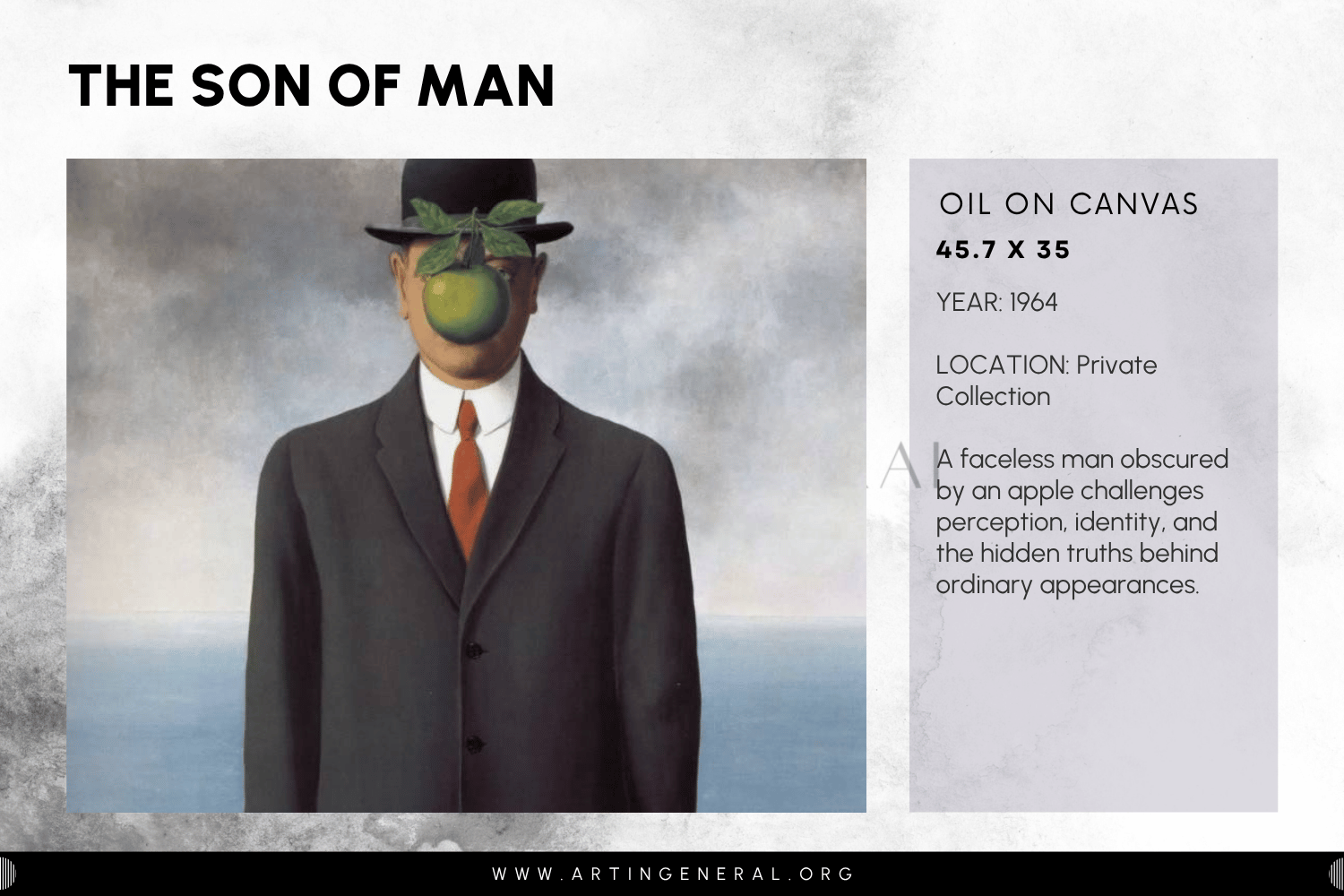

The Son of Man

Artist: René Magritte

Year: 1964

Medium: Oil on canvas

Location: Private collection

René Magritte’s The Son of Man is a quintessential example of his philosophical approach to Surrealism. At first glance, it appears deceptively simple: a man in a suit and bowler hat stands before a low wall, the sea and a cloudy sky behind him. Yet a green apple hovers directly in front of his face, obscuring his identity while paradoxically drawing our attention to what is hidden. Magritte often played with the tension between visibility and concealment, prompting viewers to question why we expect images to clarify rather than complicate our understanding.

The painting reflects Magritte’s lifelong inquiry into the nature of perception: what we see, what we assume, and what remains forever out of reach. By obscuring the man’s face, Magritte challenges the viewer’s desire for resolution and invites them to embrace ambiguity. The crisp realism heightens the surreal effect, transforming an everyday scene into a visual paradox. Its quiet, poised mystery has made it one of Magritte’s most enduring and widely referenced works, symbolizing the enigmatic nature of human identity.

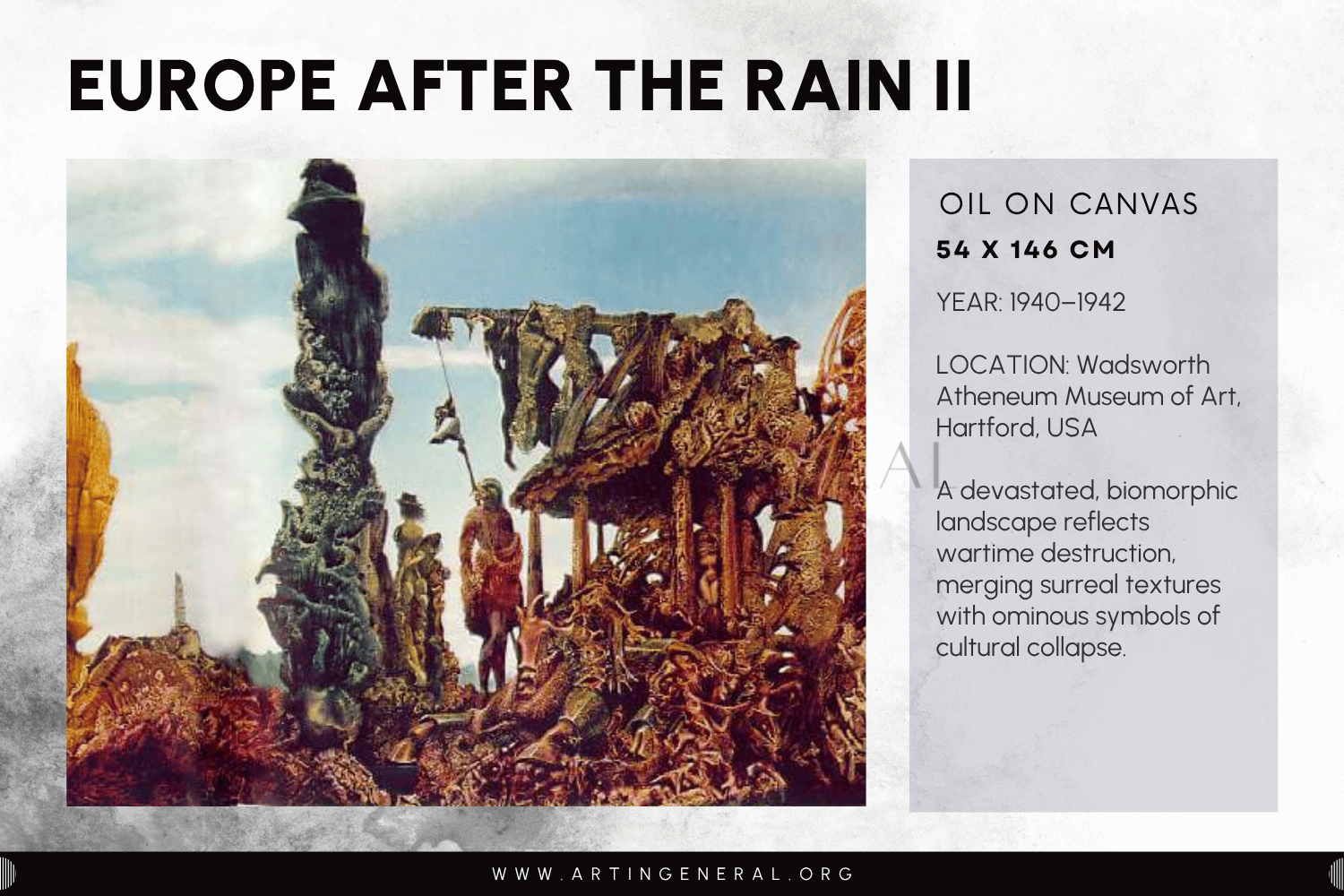

Europe After the Rain II

Artist: Max Ernst

Year: 1940–1942

Medium: Oil on canvas

Location: Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, USA

Painted during the early years of World War II, Max Ernst’s Europe After the Rain II captures the devastation of a continent facing unprecedented destruction. Created with his experimental technique of decalcomania, the work’s organic textures and branching forms suggest a landscape that has undergone violent, unnatural transformation. The resulting imagery resembles both a ruined battlefield and a strange, post-apocalyptic ecosystem, half geological, half biological.

Ernst’s composition is dense with symbolic forms that evoke decay, rebirth, mutation, and conflict. Figures appear embedded within the environment, merging with the fractured terrain as though humanity itself has been absorbed into the wreckage. The painting’s rich, layered surface invites prolonged examination; new shapes seem to emerge with every viewing, reflecting the chaotic unpredictability of wartime life.

Rather than depicting war directly, Ernst conveys its psychological impact which evokes the sense of disorientation, loss, and distorted reality. This masterpiece stands as one of Surrealism’s most political works, demonstrating the movement’s ability to engage with real-world trauma through symbolic, dreamlike means.

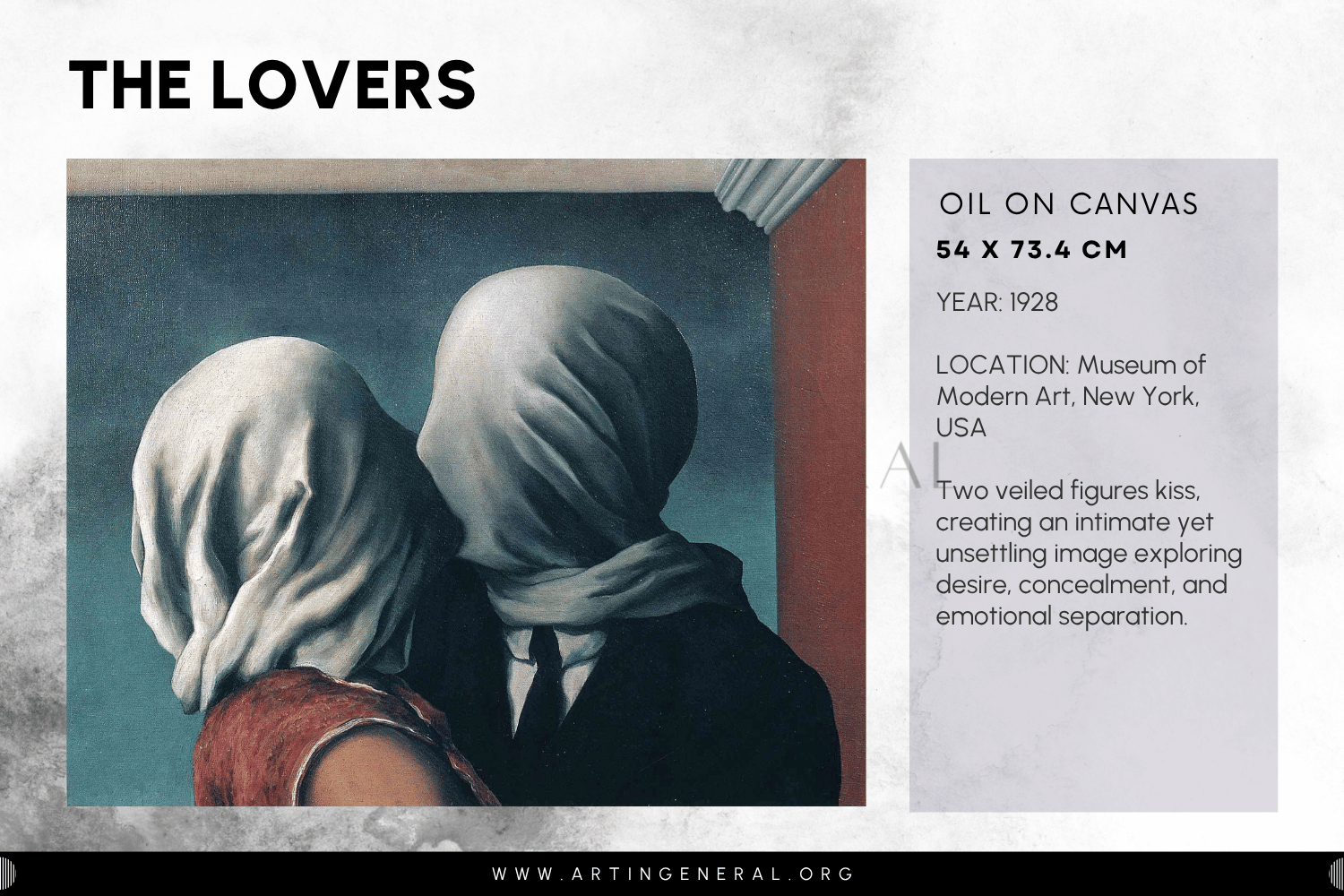

The Lovers

Artist: René Magritte

Year: 1928

Medium: Oil on canvas

Location: Museum of Modern Art, New York, USA

In The Lovers, Magritte presents an intimate yet unsettling scene: two individuals locked in a kiss, their faces completely covered by white cloth. The image is simultaneously romantic and suffocating, suggesting both longing and alienation. The shrouded faces prevent connection through sight or expression, leaving only the physical gesture which is rendered strangely impersonal by the barriers between them.

Magritte rarely offered explanations for his imagery, but scholars often point to the dualities at play: desire versus distance, presence versus absence, identity versus anonymity. The cloth becomes a symbol of the limits of intimacy, of how even in moments of closeness, individuals remain partially unknowable to one another.

The stark realism of the figures contrasts with the irrationality of their condition, creating a powerful emotional tension. Magritte’s restrained use of color and composition allows the psychological weight of the scene to take center stage. The Lovers continues to resonate because it expresses a universal truth with haunting simplicity: that connection is never fully complete, and that even love contains mysteries we cannot uncover.

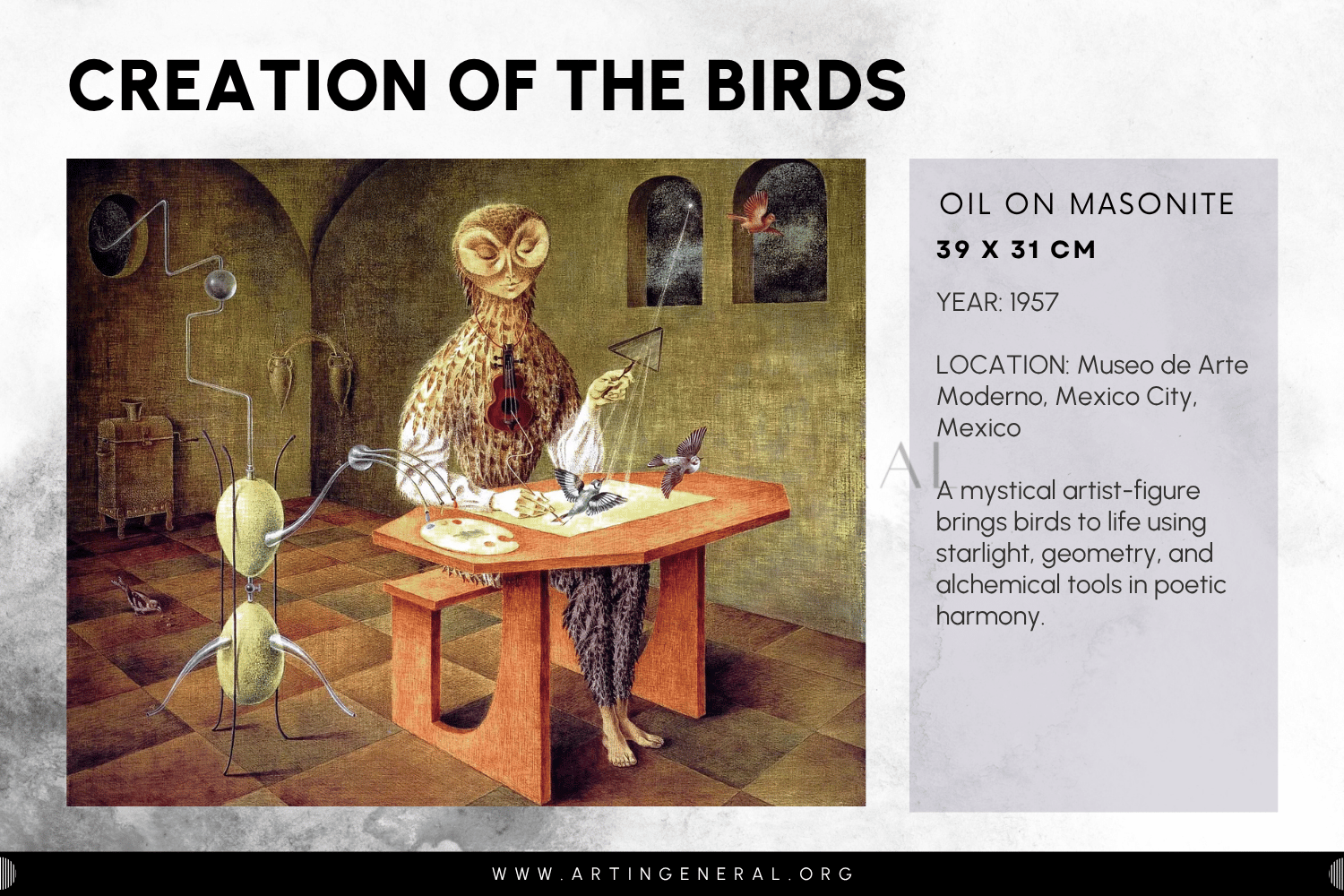

Creation of the Birds

Artist: Remedios Varo

Year: 1957

Medium: Oil on masonite

Location: Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City, Mexico

Remedios Varo’s Creation of the Birds is a luminous example of Latin American Surrealism, blending mysticism, science, and poetic imagination. The painting depicts a birdlike figure seated at a desk, carefully painting a bird that comes to life as she completes it. A mechanical apparatus, part violin and part cosmic instrument, channels starlight into her work, suggesting that creation is a fusion of intuition, knowledge, and cosmic forces.

Varo’s meticulous technique gives the scene the clarity of an illuminated manuscript, while her symbolic imagery evokes themes of creativity, transformation, and feminine wisdom. The figure’s elongated body and serene concentration contribute to the painting’s meditative atmosphere, positioning the act of creation as both sacred and scientific.

As with many of Varo’s works, the narrative is open-ended yet richly suggestive. Creation of the Birds invites viewers to contemplate the relationship between art and life, imagination and reality. It stands as one of her most celebrated pieces and as a testament to the depth and originality of women artists within the Surrealist movement.

Surrealism Beyond Europe

Although Surrealism was born in Paris, the movement’s influence quickly spread across continents, adapting to new cultural contexts and intertwining with local histories, mythologies, and artistic traditions. Outside Europe, Surrealism resonated deeply with artists who saw in it a language capable of expressing both collective trauma and personal transformation. In many regions, especially the Americas where it evolved into something fluid, hybrid, and richly symbolic.

Surrealism in Latin America

Latin America embraced Surrealism with extraordinary vitality. Writers like André Breton believed that the region’s cultural landscape which was shaped by indigenous cosmologies, colonial histories, magic, mysticism, and syncretic beliefs was inherently Surrealist in spirit. This was not meant as an exoticizing gesture; rather, he saw in its traditions a natural affinity for the dreamlike, the symbolic, and the uncanny.

Mexico became a particularly important center. After the turmoil of the Spanish Civil War and World War II, artists such as Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo, and Gunther Gerzso found a new home there, where Surrealism flourished in dialogue with myth, alchemy, ritual, and local folklore. Even though Frida Kahlo rejected the label of Surrealism, her imagery was filled with dreams, bodily transformation, and psychological intensity, admired by Breton, who saw her as a natural fit for the movement.

Across the region, Surrealism became a tool for exploring identity, politics, womanhood, and spiritual transformation, giving rise to some of the most original and influential works of the entire movement.

North America and the United States

In the United States, Surrealism took root primarily through exhibitions and the arrival of European artists fleeing the war. The 1936 Fantastic Art, Dada, and Surrealism exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art introduced American audiences to the movement’s possibilities.

This influx of ideas played a crucial role in shaping Abstract Expressionism. Artists like Arshile Gorky, Jackson Pollock, and Mark Rothko were inspired by Surrealist automatism, gesture, and psychological depth. Pollock, for instance, explored automatic drawing in his early work before developing his signature drip technique.

Surrealism in the U.S. was less unified than in Europe, but its influence on American modern art was profound and enduring.

The Global Spread

Surrealism’s reach extended far beyond the Western world. Artists in Japan, Egypt, the Caribbean, and the Middle East incorporated Surrealist strategies to comment on social upheaval, colonial histories, and national identity.

In Cairo, the Art and Liberty Group used Surrealism to criticize oppression and promote artistic freedom. In the Caribbean, writers and artists blended Surrealism with anti-colonial thought, birthing what is now called négritude surrealism.

These global reinterpretations demonstrate Surrealism’s adaptability and explain why the movement remains relevant today: it offers a vocabulary for expressing inner life while confronting outer realities.

Dada vs Surrealism

Surrealism’s earliest roots lie in Dada, an anti-art movement formed during World War I. Dada rejected logic, tradition, and bourgeois values, turning instead to chance, absurdity, and protest. Its artists used performance, collage, and spontaneity to critique the society that had produced the war.

While Dada was intentionally chaotic and nihilistic, Surrealism sought to harness the same rebellion and redirect it toward creation. Instead of destroying meaning, Surrealism wanted to uncover deeper truths hidden beneath the surface of rational thought. In short:

- Dada dismantled the old world

- Surrealism searched for a new one

This transition marks one of the most important shifts in early modernism.

Surrealism’s Influence on Abstract Expressionism

When Surrealist artists migrated to the United States during World War II, they brought with them ideas that profoundly shaped American painting. Automatism, gesture, symbolism, and the exploration of the subconscious became foundational elements of Abstract Expressionism.

Artists such as Arshile Gorky used Surrealist biomorphism as a bridge toward abstraction, while Jackson Pollock experimented with automatic drawing before developing his radical drip technique. Even Rothko’s color fields echo the Surrealists’ interest in emotion and psychological depth.

Thus, Surrealism acted as a bridge between European avant-garde innovation and the rise of New York as the center of the art world.

Surrealist Echoes in Contemporary Culture

Surrealism’s influence is so widespread that many contemporary art forms, not to mention advertising and pop culture carry its signature. Modern film directors such as David Lynch, Guillermo del Toro, and Jan Švankmajer use Surrealist imagery to explore dream logic, trauma, and identity.

In digital art, video games, fashion, photography, and even internet humor, Surrealist strategies are used like unexpected juxtapositions, dream sequences, and uncanny symbolism which are now common visual tools.

The movement’s lasting power lies in its invitation to explore the irrational, the emotional, and the mysterious. Today, Surrealism is not just an art style; it is a way of thinking about creativity.

The Legacy of Surrealism

Surrealism reshaped the course of modern art by proposing a radical idea: that creativity reaches its fullest expression when it escapes rational control. What began as a literary experiment in 1920s Paris evolved into a global movement that challenged traditional boundaries of art, psychology, and imagination. Its legacy continues to unfold today, not only in museums but across contemporary culture.

The movement left an especially strong mark on 20th-century painting. Surrealist automatism laid the groundwork for the expressive freedom of Abstract Expressionism, while hyperrealist Surrealists influenced generations of artists exploring illusion, paradox, and psychological symbolism. Surrealism’s fascination with dreams, memories, and inner life helped shift artistic focus from the external world to the complexities of the human mind.

Beyond the visual arts, Surrealism deeply impacted literature, theater, film, photography, and design. Filmmakers such as Luis Buñuel, Andrei Tarkovsky, David Lynch, and Jan Švankmajer drew from Surrealist ideas to create cinematic worlds infused with mystery and dream logic. In contemporary media, advertising, digital art, fashion, and music videos regularly employ Surrealist imagery like levitating figures, impossible landscapes, and uncanny juxtapositions demonstrating the movement’s enduring appeal.

Perhaps the movement’s greatest contribution is its liberating philosophy. Surrealism encourages viewers to trust intuition, embrace ambiguity, and question the rules that govern perception. It asks us to look inward and recognize the richness of the subconscious. Nearly a century after its founding, Surrealism remains a powerful reminder that creativity thrives where reason ends and imagination begins.

References & Further Reading

(You can expand this section depending on your final citations and any footnotes you plan to include. Below is a clean, professional Chicago-style structure you can build on.)

- Books & Academic Sources

Breton, André. Manifesto of Surrealism. Paris: Éditions du Sagittaire, 1924.

Ades, Dawn. Surrealism. London: Thames & Hudson, 1994.

Balakian, Anna. Surrealism: The Road to the Absolute. New York: Noonday Press, 1959.

Caws, Mary Ann, ed. Surrealism: Themes and Movements. London: Phaidon, 2004.

Hopkins, David. Dada and Surrealism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Spies, Werner. Max Ernst: Collages. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1991.

Chadwick, Whitney. Women Artists and the Surrealist Movement. Boston: Little, Brown, 1985.

- Museum & Institutional Resources

Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). “The Persistence of Memory.” Collection Online.

Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art. “Europe After the Rain II.” Archives & Collections.

Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City. “Remedios Varo: Selected Works.”

Centre Pompidou. “Surrealism: Artworks and Archives.”

- Articles & Essays

Ades, Dawn. “Surrealism and Its Histories.” Oxford Art Journal 7, no. 1 (1984): 18–25.

Caws, Mary Ann. “The Poetry of Surrealism.” Comparative Literature Studies 40, no. 3 (2003): 336–349.

Gaillard, Aurélie. “Leonora Carrington and the Magic of Transformation.” Art History Review, 2017.

- Online Sources (for contextual support)

The Met Museum – Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History: Surrealism

Tate Modern – Surrealism Movement Overview

Art Institute of Chicago – Essays on Surrealist Practices

Leave a Reply