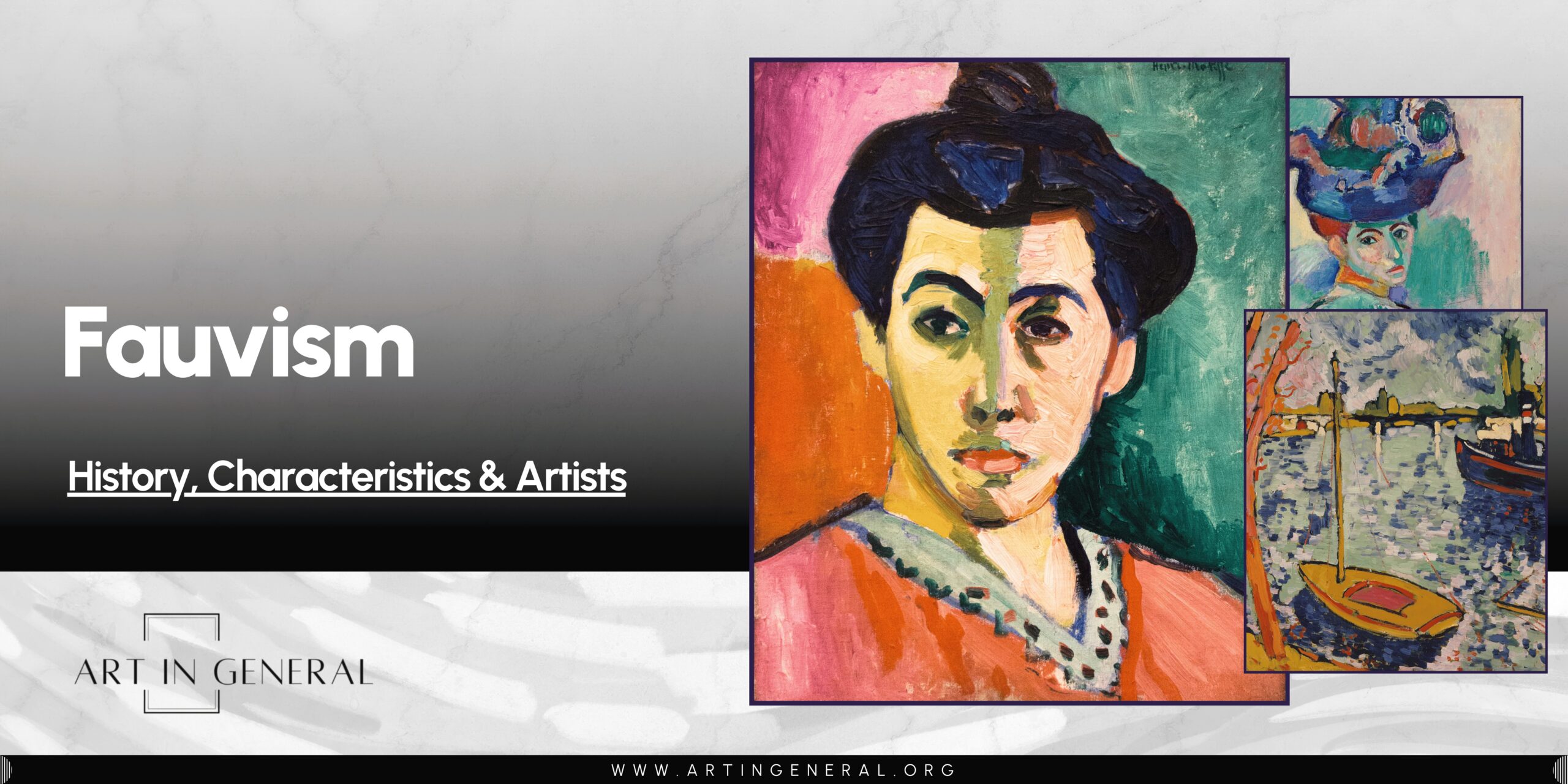

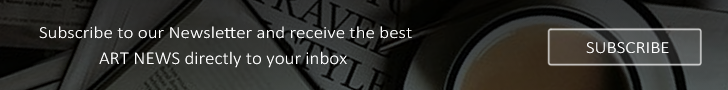

Fauvism was the first major avant-garde movement of the 20th century, a brief but explosive revolution that transformed the role of color in modern art. Emerging in France around 1905, the Fauves (Henri Matisse, André Derain, Maurice de Vlaminck, and their circle) rejected naturalistic color and traditional modeling. Instead, they embraced pure pigment, expressive brushwork, and simplified forms to convey emotion rather than visual accuracy.

Fauvism was the first major avant-garde movement of the 20th century, a brief but explosive revolution that transformed the role of color in modern art. Emerging in France around 1905, the Fauves (Henri Matisse, André Derain, Maurice de Vlaminck, and their circle) rejected naturalistic color and traditional modeling. Instead, they embraced pure pigment, expressive brushwork, and simplified forms to convey emotion rather than visual accuracy.

The movement earned its name after the 1905 Salon d’Automne, where a group of critics reacted with shock to the vivid canvases on display. One reviewer, Louis Vauxcelles, famously called the artists “les fauves,” or “the wild beasts,” a label that captured both the intensity and the freedom of their approach.

Though Fauvism lasted only a few years, its impact was profound. It marked a decisive break from Impressionism and Post-Impressionism and set the stage for future modern movements like Expressionism, Cubism, and abstraction by liberating color from realism and demonstrating art’s capacity to prioritize emotion, structure, and personal vision above optical truth.

Origins of the Fauvist Movement

Post-Impressionism and the Rise of Expressive Color

Fauvism did not appear out of nowhere; it emerged from a rich lineage of artists who had already begun pushing color beyond realism. Post-Impressionists such as Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, and Paul Cézanne profoundly influenced the younger generation of Fauves.

- Van Gogh showed that color could be emotional, even spiritual.

- Gauguin demonstrated the power of flattened shapes and symbolic palettes inspired by non-Western art.

- Cézanne reduced nature to simplified, structural forms setting a foundation for both Matisse and the future Cubists.

- Georges Seurat and Paul Signac introduced Divisionism/Pointillism, proving that color could be broken down, intensified, and rebuilt scientifically.

By 1900, these ideas were converging in the minds of a younger generation ready to break traditions entirely. The Fauves absorbed these influences but took them to a radical extreme, using pure colors directly from the tube, high contrast, and simplified forms to create unprecedented visual impact.

The 1905 Salon d’Automne: Birth of the “Wild Beasts”

The defining moment of Fauvism took place at the 1905 Salon d’Automne in Paris. In Room VII, the walls were covered with works by Matisse, Derain, Vlaminck, Manguin, and Camoin. Multiple canvases filled with unnatural greens, fiery reds, and shocking blues.

These pieces were placed beside a classical sculpture by Albert Marque and the contrast was dramatic. Critic Louis Vauxcelles remarked:

“Donatello chez les fauves!”

“Donatello among the wild beasts!”

The press seized the phrase immediately. What had been intended as an insult became a badge of honor. Overnight, this loosely connected group of painters became known as the Fauves.

While the public was divided between some outraged fellows and others fascinated, the exhibition marked the beginning of modern art’s break with the naturalistic traditions of the 19th century.

A Movement Without a Manifesto

Unlike Surrealism or Cubism, Fauvism had no official manifesto, no theory to defend, and no leader issuing rules. Yet its artists shared clear values:

- Color came first, liberated from nature.

- Form was simplified, flattened, or distorted.

- Brushwork was energetic, direct, and intuitive.

- Art was meant to express emotion, sensation, and joy, not realism.

The Fauves were united more by personal friendship and shared experimentation than by ideology. Their loose alliance lasted only until around 1908, when many members, especially Derain and Braque moved toward Cubism. But in just a few years, they opened the door to nearly every major modernist movement that followed.

Characteristics of Fauvist Art

Fauvism is instantly recognizable for its vibrant palette and bold, spontaneous energy. Although the movement was short-lived, its visual language was radical for its time and redefined the expressive potential of painting. Fauvist artists believed that color could communicate emotions more powerfully than naturalistic representation, and they embraced simplification, directness, and intuition over traditional academic technique.

Below are the core characteristics that shaped Fauvist painting and gave it its unforgettable visual impact.

Explosive, Non-Naturalistic Color

Color is the heartbeat of Fauvism. Instead of depicting the world realistically, the Fauves chose hues based on how they felt: a face might appear green, shadows purple, and skies blazing orange. This use of pure, unmixed pigment created intense visual contrasts that emphasized emotion rather than observation. Influenced by Post-Impressionists like Gauguin and Van Gogh, the Fauves pushed chromatic freedom to new extremes.

Bold, Expressive Brushwork

Fauvist paintings often appear raw and immediate, as if completed in a single burst of energy. Brushstrokes remain visible, vigorous, and deliberately unrefined. Artists like Vlaminck and Derain relied on thick application and sweeping marks, allowing texture and gesture to become expressive elements in their own right. The result is a sense of movement and vitality that animates even quiet scenes.

Simplification and Flattening of Form

Rather than modeling forms through shading or careful transitions, Fauvist artists simplified shapes into large, unified areas of color. This flattening which was often influenced by Japanese prints, medieval art, and African sculpture created strong compositions that emphasized structure over detail. Matisse, in particular, believed in using “the minimum of lines and colors” to achieve the greatest emotional effect.

Liberation from Naturalism

Fauvism marked a decisive break from the Impressionist commitment to capturing the effects of natural light. Instead of harmonizing colors to reflect reality, Fauves used color arbitrarily or symbolically. This shift helped free painting from the expectations of realism and opened the door to abstraction, Cubism, and modern design theory.

Emotional Intensity and Sensory Impact

The Fauves often aimed to convey joy, energy, warmth, and sensation. Landscapes glow with unnatural colors, and portraits pulse with expressive force. While not typically concerned with the darker emotions explored by later Expressionists, the Fauves sought to evoke an immediate emotional response using color as pure sensation.

Influence of Primitivism and “Exotic” Aesthetics

Many Fauvist artists admired African, Oceanic, and Islamic art for its bold simplifications and symbolic forms. This influence is visible in their approach to shape, ornament, and color. While these interests were shaped by the colonial attitudes of the era, they contributed significantly to the movement’s break from Western academic traditions.

Which Painting Techniques Were Used in Fauvist Painting?

Although Fauvist paintings appear spontaneous, they are rooted in deliberate choices about color, composition, and material. The techniques developed during this period helped define modern painting for decades to come.

- Unmixed Pigments: Fauvist painters frequently used pigments directly from the tube, avoiding the muted tones produced by mixing. This technique created strong visual contrasts and amplified the emotional power of color. Matisse described this approach as letting color act “as a force, not as a description.”

- High-Contrast: The Fauves often paired complementary hues (red/green, blue/orange, yellow/purple) to intensify their vibrancy. These combinations pull the viewer’s eye across the canvas and generate dynamic movement within the composition. Painters like Derain used this method extensively in their landscapes.

- BroadAreas of Color: Instead of modeling form through shading, Fauvist artists used flat or nearly flat color fields to structure their compositions. Shadows might be painted blue; highlights might be orange. This approach simplifies forms and emphasizes the painting’s surface, rather than illusionistic depth.

- Intuitive Drawing: Drawing was integrated into the painting process through loose, gestural lines. Artists often outlined figures or objects in dark strokes, sometimes black, sometimes with complementary colors to create rhythm and contrast. This technique contributed to the movement’s graphic quality.

- Direct Execution: Fauvist paintings were often completed rapidly, sometimes outdoors, to maintain spontaneity and energy. This immediacy is visible in the rough edges, visible strokes, and vibrant surfaces that became hallmarks of the movement.

Key Fauvist Artists

Though Fauvism lasted only a few years, its core group of painters reshaped the direction of modern art. Each artist contributed something distinct through pure color, bold structure, or emotional force. Below are the most influential figures who defined the movement and carried its spirit into later phases of their careers.

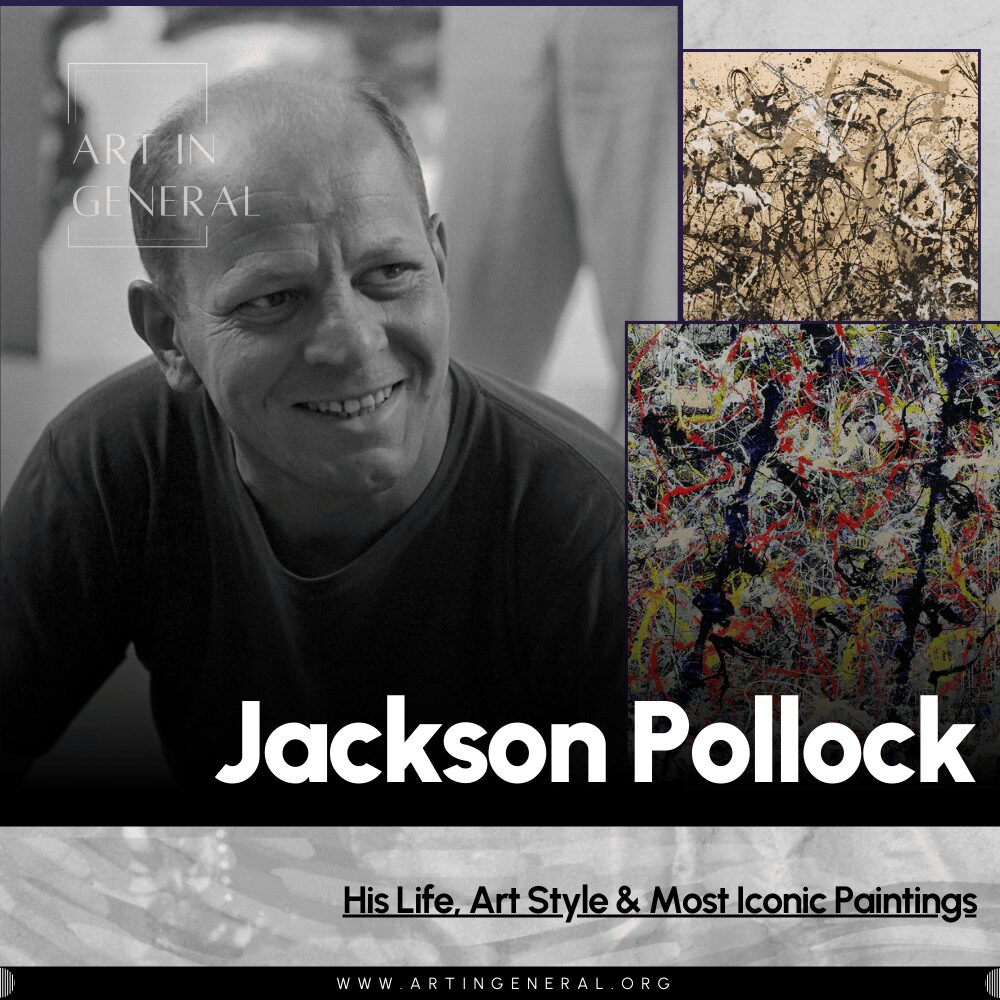

Henri Matisse (1869–1954)

- Born: December 31, 1869, Le Cateau-Cambrésis, France

- Died: November 3, 1954 (aged 84), Nice, France

- Nationality: French

- Education: Académie Julian; École des Beaux-Arts

- Most Known Works:

- The Dance (1910)

- The Red Room (1908)

- Blue Nude (1907)

Henri Matisse is the best-known figure of Fauvism and the artist who gave the movement its emotional depth and intellectual foundation. Originally trained in academic realism, Matisse gradually moved toward expressive color after studying the works of Van Gogh, Gauguin, and Cézanne. By 1905, his palette had become fiercely vibrant, his forms simplified, and his brushwork bold yet controlled.

Matisse believed that color could act as a direct emotional language. He used greens to model faces, hot reds to animate interiors, and unmodulated blues to create atmosphere. His Fauvist period marks a turning point in modern art, where color no longer represented reality but instead conveyed sensation, harmony, and personal vision.

André Derain (1880–1954)

- Born: June 10, 1880, Chatou, France

- Died: September 8, 1954 (aged 74), Garches, France

- Nationality: French

- Education: Académie Camillo; studied with Maurice de Vlaminck

- Most Known Works:

- Charing Cross Bridge (1906)

- The Turning Road, L’Estaque (1906)

Alongside Matisse, André Derain was instrumental in shaping the movement’s explosive palette and dynamic compositions. In the summer of 1905, Derain and Matisse worked together in Collioure, producing some of Fauvism’s most iconic landscapes. Derain pushed color intensity even further than Matisse, using oranges, ultramarines, acid greens, and hot pinks to reinterpret light.

Derain’s London series (1906–07), commissioned by Ambroise Vollard, transformed the city’s fog into radiant color harmonies turning gray bridges and misty skies into electric compositions. Although Derain later moved toward a more classical style, his Fauvist period represents some of the movement’s boldest achievements.

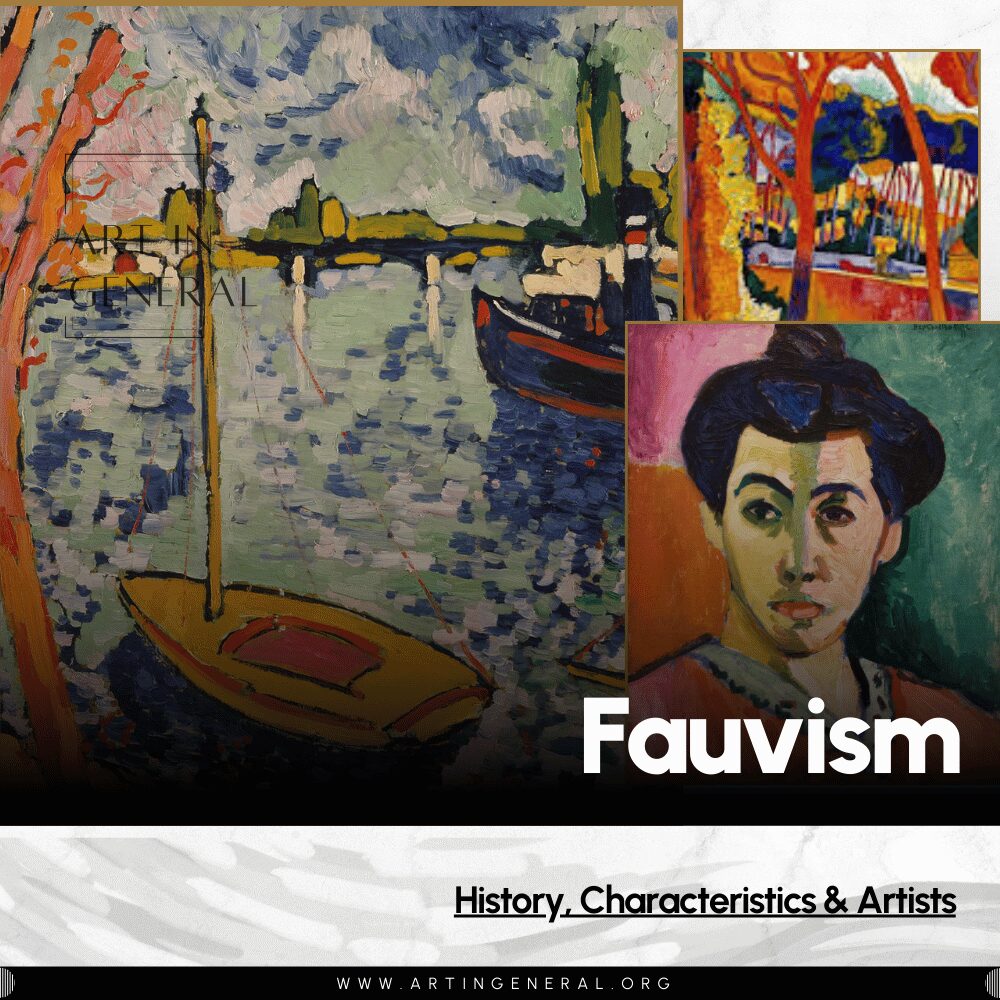

Maurice de Vlaminck (1876–1958)

- Born: April 4, 1876, Paris, France

- Died: October 11, 1958 (aged 82), Rueil-la-Gadelière, France

- Nationality: French

- Education: Mostly self-taught; informal study with Derain

- Most Known Works:

- The River Seine at Chatou (1906)

- Barges on the Seine (1905–06)

Self-taught and fiercely individualistic, Vlaminck brought raw, emotional force to Fauvism. More instinctive than analytical, he often painted rapidly, using thick strokes and pure pigments to create turbulent landscapes full of passion and energy. His early works from Chatou and the Seine region are among the most intense of the movement, characterized by fiery reds, electric blues, and dramatic contrasts.

Vlaminck valued instinct above theory and famously said he wanted to burn down the École des Beaux-Arts. His commitment to emotional expression made him one of the purest Fauves.

Raoul Dufy (1877–1953)

- Born: June 3, 1877, Le Havre, France

- Died: March 23, 1953 (aged 75), Forcalquier, France

- Nationality: French

- Education: École des Beaux-Arts, Paris

- Most Known Works:

- Regatta at Cowes (1934)

- La Fée Électricité (1937)

Raoul Dufy brought a joyful, decorative sensibility to Fauvism, combining bright color with graceful line. While initially influenced by Matisse, Dufy quickly developed his own light-filled aesthetic characterized by breezy compositions, seaside scenes, and lively patterns. His later work in textiles and interior design expanded Fauvism into the world of applied arts.

Kees van Dongen (1877–1968)

- Born: January 26, 1877, Delfshaven, Netherlands

- Died: May 28, 1968 (aged 91), Monte Carlo, Monaco

- Nationality: Dutch-French

- Education: Royal Academy of Fine Arts, Rotterdam

- Most Known Works:

- Woman with Large Hat (1906)

- The Corn Poppy (1919)

Van Dongen brought glamour and sensuality to Fauvism. Known for his portraits of Parisian nightlife with cabarets, dancers, and fashionable women as main themes, he used intense colors and elongated forms to heighten expressiveness. His bold reds and greens often served to emphasize eroticism, elegance, or psychological tension.

Georges Braque (1882–1963)

- Born: May 13, 1882, Argenteuil, France

- Died: August 31, 1963 (aged 81), Paris, France

- Nationality: French

- Education: Académie Humbert

- Most Known Works:

- Houses at L’Estaque (1908)

- Violin and Candlestick (1910)

Before co-founding Cubism with Picasso, Georges Braque had a brief but meaningful Fauvist phase. His landscapes from L’Estaque use bright color blocks and simplified forms that foreshadow the geometric structure of early Cubism. Braque’s Fauvist works demonstrate how the movement’s formal experimentation laid groundwork for abstraction.

Masterpieces of Fauvism

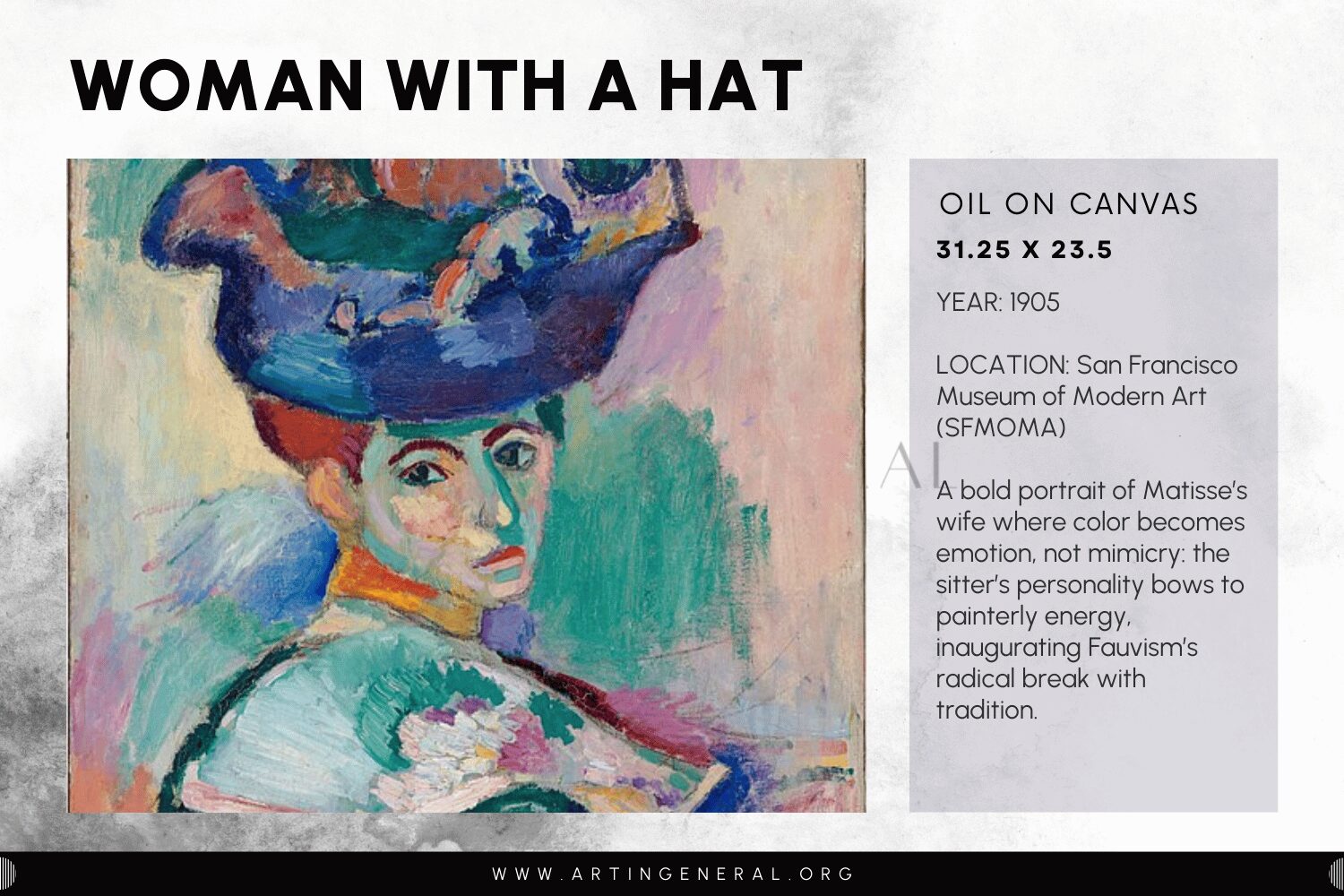

Woman with a Hat

- Artist: Henri Matisse

- Year: 1905

- Medium: Oil on canvas

- Dimensions: 79.4 cm × 59.7 cm (31.25 in × 23.5 in)

- Location: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco

Woman with a Hat is one of the most iconic works of Fauvism and the painting that caused the 1905 Salon scandal. The portrait depicts Matisse’s wife, Amélie, yet it abandons traditional realism entirely. Her face is rendered with broad strokes of green, blue, lilac, orange, and yellow, colors chosen not for natural accuracy but for emotional vibrancy. The brushwork is loose, varied, and spontaneous, giving the portrait an energetic surface that seems to shimmer with light.

What shocked critics most was Matisse’s total refusal to harmonize the palette. Instead, he used clashing hues to create a dynamic and expressive tension, challenging long-held expectations of beauty and representation. The hat, with its explosion of patterned color, becomes a visual anchor that reinforces the painting’s bold modernity.

This work encapsulates the Fauvist belief that color could stand alone and act as pure emotion. It remains one of the most radical portraits of the early 20th century.

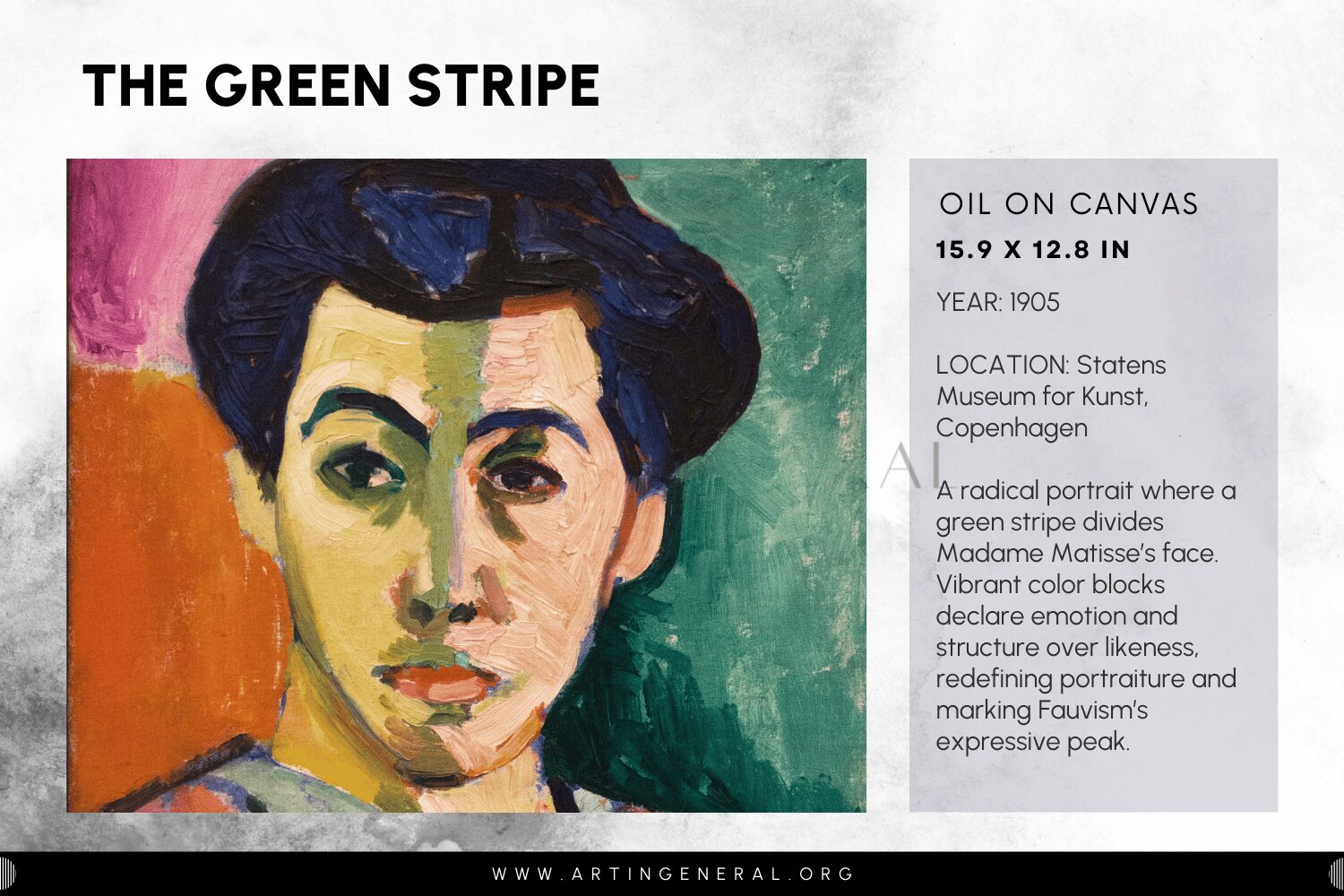

The Green Stripe (Portrait of Madame Matisse)

- Artist: Henri Matisse

- Year: 1905

- Medium: Oil on canvas

- Dimensions: 40.5 cm × 32.5 cm (15.9 in × 12.8 in)

- Location: Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen

The Green Stripe is a masterpiece of Fauvist portraiture and a pivotal turning point in Matisse’s artistic evolution. The painting is named for the bold vertical line of green that divides Amélie Matisse’s face, effectively replacing traditional shading with a single stroke of pure color. This daring decision demonstrates Matisse’s belief that color relationships could define form and emotion.

The background contrasts hot reds and cool greens, enveloping the figure in an expressive chromatic environment. Amélie’s facial features are simplified and stylized, while her dress and hat are depicted with confident, rhythmic brushstrokes. The portrait is not meant to capture likeness, but rather the emotional presence of the sitter through a harmonious yet unexpected palette.

At the time, critics saw it as a provocation; today, it is understood as a foundational statement of modern art. The Green Stripe exemplifies how Fauvism shifted painting toward expressive abstraction and away from traditional representation.

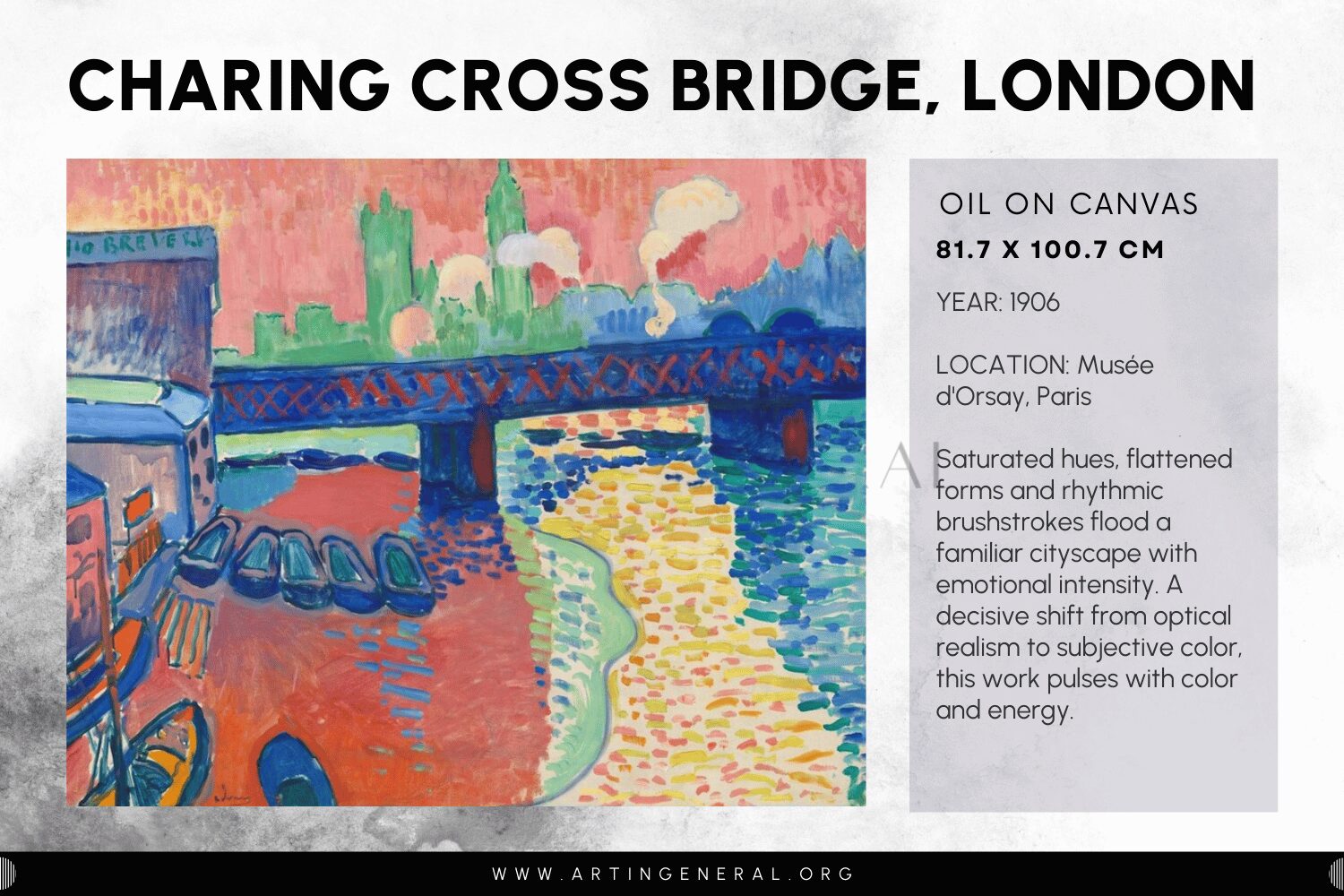

Charing Cross Bridge, London

- Artist: André Derain

- Year: 1906

- Medium: Oil on canvas

- Dimensions: 81.7 cm × 100.7 cm (32.125 in × 39.625 in)

- Location: Musée d’Orsay, Paris

In Charing Cross Bridge, Derain transforms the foggy London landscape into a dazzling kaleidoscope of color. Painted during a period when the artist was exploring how far he could push chromatic intensity, the Thames becomes a ribbon of orange and yellow, while the bridge glows in deep blue and violet. The sky, rendered in complementary hues, vibrates with energy.

Derain’s London series was groundbreaking because it reimagined a famously gray city through pure sensation rather than observation. His use of unmixed pigments and simplified geometric forms foreshadows later modernist abstraction. The thick, expressive brushwork suggests immediacy and confidence, capturing the movement’s instinctive spirit.

The painting embodies the Fauvist belief that color could create light, mood, and atmosphere independently from nature. Rather than depicting London realistically, Derain presents a city transformed by artistic imagination.

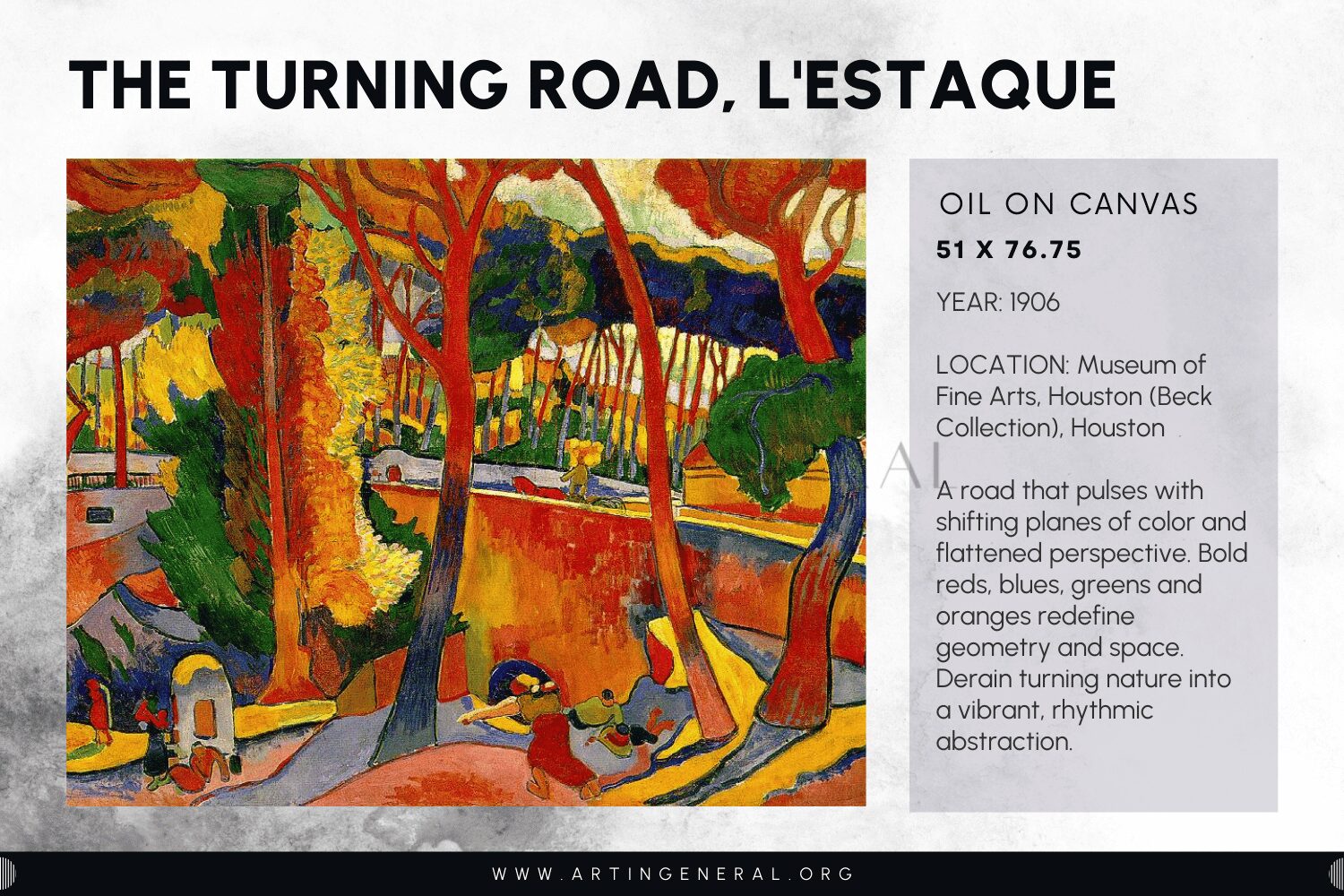

The Turning Road, L’Estaque

- Artist: André Derain

- Year: 1906

- Medium: Oil on canvas

- Dimensions: 129.5 cm × 194.9 cm (51 in × 76.75 in)

- Location: Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

The Turning Road, L’Estaque is one of Derain’s most celebrated Fauvist landscapes, painted in the Mediterranean village where Cézanne once worked. Derain uses intense complementary colors to construct the composition. The scene is organized into large planes of color, creating a structure that feels both architectural and rhythmic.

The landscape is simplified into bold shapes, with houses, roads, and trees reduced to graphic forms. The colors do not correspond to nature; instead, they create a dazzling chromatic architecture that expresses the heat and luminosity of southern France. Derain’s brushwork is confident and energetic, giving the painting a sense of immediacy and movement.

This work demonstrates how Fauvism used color not just to enhance a scene, but to rebuild it entirely. The painting captures the essence of place through emotional force rather than literal depiction, making it one of the clearest expressions of the Fauvist vision.

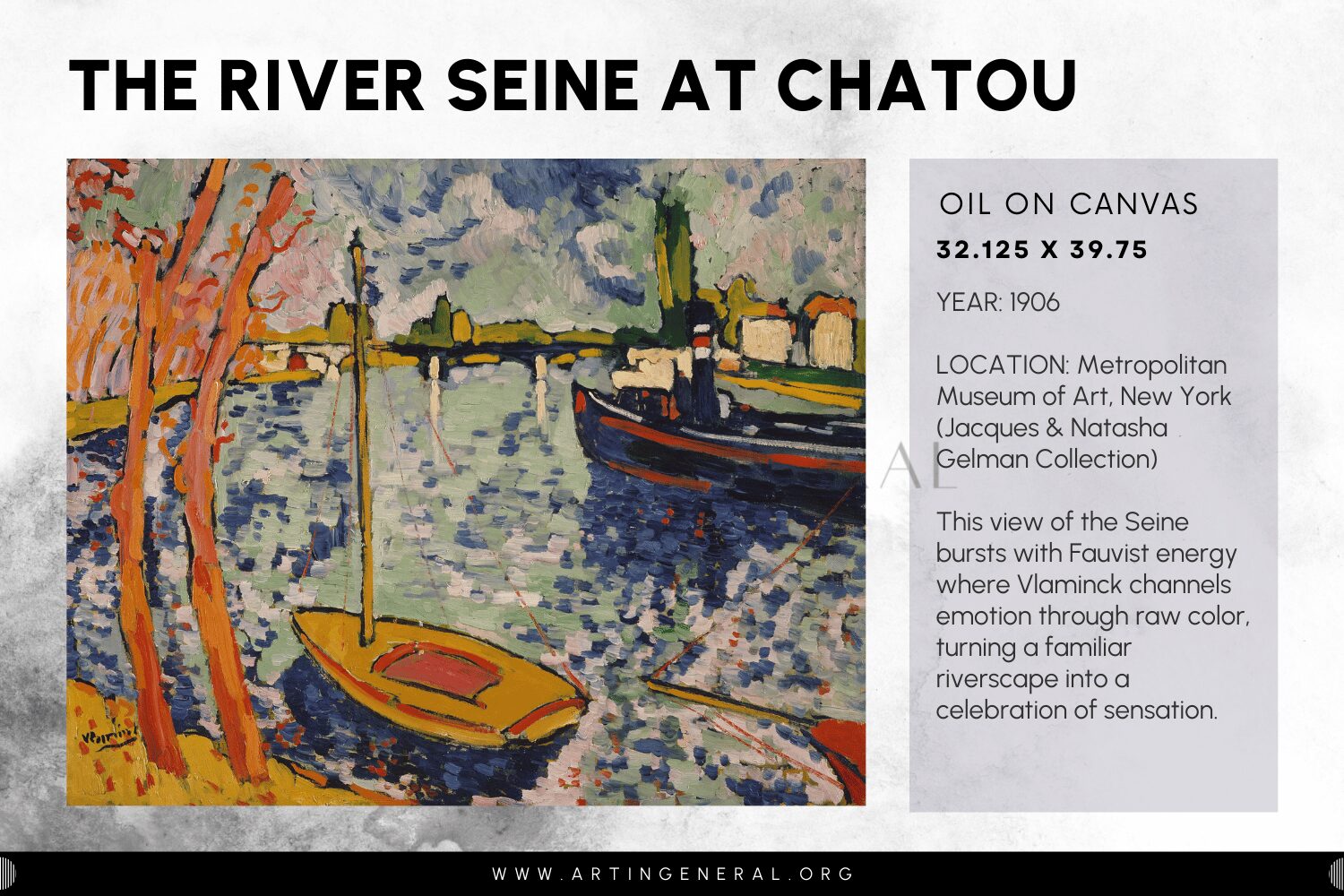

The River Seine at Chatou

- Artist: Maurice de Vlaminck

- Year: 1906

- Medium: Oil on canvas

- Dimensions: 81.6 cm × 101 cm (32.125 in × 39.75 in)

- Location: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The River Seine at Chatou exemplifies Vlaminck’s raw, intuitive approach to Fauvist color. Painting the suburban landscape near his home, Vlaminck reinterprets the river and surrounding village through fierce strokes of cobalt blue, vermilion, cadmium yellow, and emerald green. The contrast between these saturated hues generates tension and emotional intensity.

Unlike Matisse’s carefully balanced harmonies, Vlaminck’s colors feel eruptive and immediate. His brushwork is thick, sometimes nearing impasto, conveying urgency and passion. The sky, rendered as a swirling mass of contrasting tones, amplifies the drama of the scene.

This painting showcases the wilder edge of Fauvism, more instinctive and less controlled than Derain’s or Matisse’s approaches, but reflects Vlaminck’s belief in painting as an emotional explosion

Fauvism and Other Art Movements

Fauvism sits at a pivotal crossroads in the history of modern art. Though brief, its radical approach to color and form created a bridge between the innovations of the late 19th century and the abstraction that would define the 20th. Understanding its relationship to surrounding movements helps clarify why its impact was so enduring.

From Impressionism to Fauvism

Impressionism had already challenged academic norms by prioritizing light, atmosphere, and momentary sensation. However, Fauvism diverged from Impressionism in several crucial ways:

- Color became expressive rather than descriptive.

Impressionists used color to capture natural light; Fauves used it to convey emotion. - Brushwork became more forceful and direct.

Instead of flickering strokes that dissolve forms, Fauvist marks emphasize structure and energy. - Form was simplified rather than observed.

Impressionists painted what they saw; the Fauves painted what they felt.

In shifting from optical realism toward emotional expression, Fauvism marked the beginning of a new modernist language, one where subjective experience mattered more than visual accuracy.

Fauvism vs. Expressionism

Although Fauvism and German Expressionism emerged around the same time, they reflect different emotional attitudes:

- Fauvism emphasizes joy, warmth, and chromatic freedom.

- Expressionism embraces psychological intensity, anxiety, and distortion.

Both movements use non-naturalistic color, but whereas Fauves saw color as a celebration, Expressionists often used it to channel inner turmoil. Nevertheless, the two groups deeply influenced one another. The bold palettes and liberated brushwork of the Fauves helped artists of Die Brücke and Der Blaue Reiter push their own innovations further.

Fauvism Leads to Cubism

One of the clearest legacies of Fauvism lies in its contribution to the early development of Cubism. As painters like Georges Braque and (briefly) Derain began simplifying forms into larger, flatter color zones, they grew increasingly interested in structure and geometry.

This shift from color towards form prepared the ground for Cubism’s radical break with representation. Cézanne provided the theoretical framework; Fauvism accelerated the simplification. The result was one of the most transformative movements of the century.

Legacy of Fauvism

Although Fauvism lasted only from about 1905 to 1908, its legacy is disproportionately vast. The movement fundamentally redefined the role of color in painting, proving that it could serve as an independent expressive force rather than a tool for naturalistic description. This idea became foundational for modern art.

Matisse continued to refine Fauvist principles throughout his life, applying them to interiors, odalisques, and later his groundbreaking cut-outs. His belief in “a harmony parallel to nature” inspired generations of colorists. Artists like Pierre Bonnard, Marc Chagall, and later David Hockney drew deeply from Fauvist chromatic sensibilities.

Fauvism also revolutionized design. Raoul Dufy’s decorative interpretation of the movement influenced 20th-century textiles, printmaking, and interior design. In contemporary culture, Fauvist color can be seen in illustration, graphic design, and digital media where high-saturation palettes and bold contrasts remain central tools of visual impact.

More broadly, Fauvism’s liberation of form, brushwork, and expressive immediacy paved the way for major movements including Expressionism, Cubism, Abstract Expressionism, and Color Field painting. Its energetic optimism and fearless palette continue to resonate with artists seeking to prioritize intuition and emotion.

Fauvism may have been a short-lived experiment, but it marked the beginning of modernism’s boldest transformations, and its echoes still color the way we see the world today.

References & Further Reading

Books & Academic Sources

Blunt, Anthony. Modern Painters and Their World. New York: Harper & Row, 1966.

Elderfield, John. Henri Matisse: A Retrospective. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1992.

Freeman, Julian. Fauvism. London: Tate Publishing, 1996.

Gowing, Lawrence. Matisse. New York: Oxford University Press, 1979.

Whitfield, Sarah. Fauvism. London: Thames & Hudson, 1991.

Rewald, John. Post-Impressionism: From Van Gogh to Gauguin. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1956.

Museum & Institutional Resources

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA). Woman with a Hat Collection Entry.

Statens Museum for Kunst. “Portrait of Madame Matisse (The Green Line).”

National Gallery of Art. Charing Cross Bridge – André Derain.

Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. The Turning Road, L’Estaque.

Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. Vlaminck Collection.

Articles & Essays

Whitfield, Sarah. “Fauvism Revisited.” The Burlington Magazine 122, no. 927 (1980): 724–733.

Flam, Jack. “Matisse and the Expression of Color.” Art Journal 43, no. 2 (1983): 132–139.

Leave a Reply